Ivory Coast. The three rivers.

The two ethnic groups of the Agni-Baulé in Ivory Coast have developed a particular cosmogony, a ritual and social system that deserves interest and sometimes admiration. Through legends, the Agni-Baule explain their origin.

With a population of over 27.5 million, Côte d’Ivoire has around sixty ethnic groups. The Agni – Baulé belong to the large Akan group, originating from present-day Ghana.

According to tradition, the Akan left their ancestral lands in northern Ghana to settle in the gold-rich forests of the south. Gold was used in many ways among the Akan. On the one hand, it was used for the sumptuous ornaments of the chiefs and constituted the family or royal treasure. On the other hand, it was a currency necessary for the purchase of wool from Sudan (now Mali) and dried fish from Niger.

Underlying political problems and greed for the precious metal, a sacred symbol of power, caused numerous internal wars, giving power to the nucleus of Ghana’s Ashanti (concentrated around their capital, Kumasi), while the defeated factions were forced to look for new lands elsewhere. Those who moved west (the current territory of Ivory Coast), reached the Comoé River, also settling in the plains near the Bandama River. This portion of immigrants is today known as the Agni and Baulé.

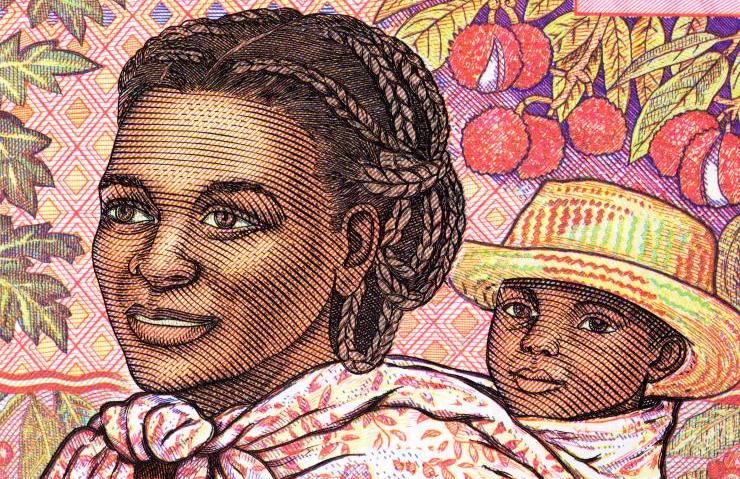

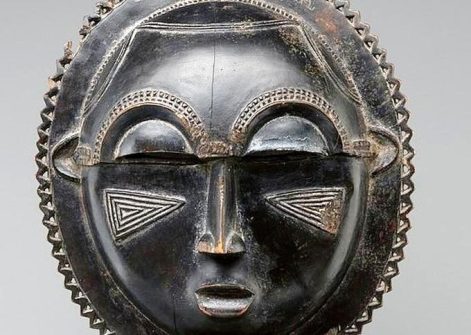

Baulé Mask. There are eight Baulé subgroups. CC0/ Clevelandart Museum

According to oral tradition, the first settlers of this migratory flow, led by the warrior chief Brindu, settled with the name of Agni Diabe (Djuablin) in the region of Assikasso, today known as Agnibilékru. The first camps, and later the first Agni villages, were established in this region.

The ethnologists Delafosse and Tauxier define the Agni complex as an ethnic conglomerate, whose main components are the Diablé or Djuablin, the N’dénié, the Sanwi or Brafé, the Moronu, the Ano, the Bini, the Bétié, the Bona and the Abi. The Agni are known not only for their great agricultural tradition but also for their love of gold. Indeed, gold panning is still one of their main occupations on several rivers that pass through the country.

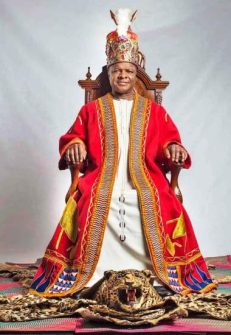

As for the Baulé, while maintaining ties with the Agni through their historical origins and a common language, they are the least culturally faithful of the Akan. This is partly explained by the influx of blood from other ethnic groups since they settled in the heart of the Ivorian savannahs. These peoples include the Alanguira or Denkyéra, who settled around 1700 and then became part of the kingdom of Baulé, the Guro or Kuéni, the Senufo and the Malinké. There are eight Baulé subgroups: the four free ones are the Uarebo, the Sâafué, the Fâfué and the N’zipri. They are accompanied by four vassal families: the Aitu, the Nananfué, the N’gban and the Agba, who found their homogeneity under the reign of the legendary queen Abla Poku.

Three River Deities

The traditional religions of Agni-Baulé can be divided into the religion of the land (celebrated by farmers in the plains and mountainous areas), the religion of pastoralism and the religion of water (Tanoé, Bia, Comoé, N’Zi, etc.). Around this theme, the Agni-Baulé have developed a particular cosmogony, a ritual and social system that deserves interest and sometimes admiration. Through a legend, the Agni-Baule explain their origin.Bia, Eholié and Tanoé are three rivers, three gods, three brothers born from the same mother and three enemies. Bia was the oldest and Tanoé the youngest. During childhood, they did not receive the same amount of affection from their elderly, blind mother.

Despite being the eldest, Bia was shy, but obedient and docile, and much loved by his mother.

Comoé River. CC BY-SA 4.0/ ETF89

Eholié, the middle child, was very fond of the old goddess. As for Tanoé, cunning, insolent and vain, he spent all his time arguing in public meetings. Gambling was his only concern.

Death, always implacable – even for the gods – came to the old woman who decided to divide her fortune among her children. She called them one after another into her smoke-filled cabin. First, she called Bia. The door opened and closed again: “My son, may God give you health, fortune and glory for all the favours you have done me in my old age. Leave this region today and go and settle southeast of the great lake. You will thus serve as a common god to two strong peoples: the Agni-Brafé and the Ashanti. You will be the object of endless worship. Great quantities of pure gold, flocks of white sheep and all the riches that men possess will come to your altar as a sign of submission and recognition. You will be the most glorious of all your companions. Go, my son. May the Almighty bless you.

The goddess took leave of her beloved son, after blessing him. Then it was the turn of the middle one. Eholié – said the old and blind mother -, death has taken me. I have little time left to live. Gather your things and go settle in Siman Forest. You loved me with infinite love. You will be marked forever with the sign of mourning that will remind you of my death. No impure woman, no funeral convoy will cross your bed. You will be a singular but feared god. The humans will trust your vigilance and offer you black goats and rams from their herds. The Brafé rulers will choose you as protector of their kingdom and will keep your commandments. In difficulties as in triumphs, you will lend a hand to Bia, your older brother.”

Baulé Mask. Bia, Eholié and Tanoé are three rivers, three gods, three brothers born from the same mother and three enemies. CC0/ Moon Mask MET

The goddess took leave of her beloved son, after embracing and blessing him. She didn’t bother calling the ungrateful Tanoé. However, the door opened: “Mother, God bless you – said a nearby voice. I just returned from the pier where I was waiting for the fishermen to arrive.”

“Who is he? “- asked the blind old woman, who lay on her bed, shaken by the anguish and suffering of death.

“I am Bia, your dearest son,” said the voice at the door. “Why haven’t you gone to your kingdom yet?” The anguished goddess asked. “I have no kingdom, mother,” the voice again replied. “But who did I talk to just now? Wasn’t it the evil Tanoé?” With what little strength she had left, she called out: “Tanoé! Tanoé! Tanoé!” But no one answered. Then she noticed that Tanoé was gone. “Yes, he is the one I gave my all; it is to Tanoé that I have bequeathed all my treasure.” The old woman shed her last tears of sorrow. To the best of her three sons, the one who had served her, their mother could only bequeath the least, the part that brought no glory. And she died of sorrow.

Bia went to tell his misfortune to his younger brother. Eholié was furious and promised him help and protection against Tanoé. Bia had occupied the cursed territory that should have belonged to Tanoé and so it became the river that drains impurities and is never invoked. But the Eholié-Bia alliance is eternal. Today, under penalty of shipwreck and being devoured by a crocodile, it is strictly forbidden to pronounce the name of Tanoé when sailing on Bia or Eholié.

The River Comoé and the Legend of Baulé

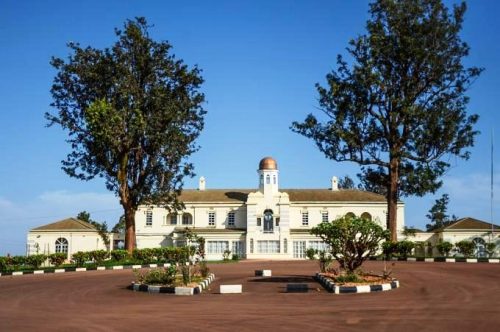

Located on the banks of the forest and savannah, the Baulé people have a history inseparable from the Comoé River, the longest in Ivory Coast

at 1,160 kilometres.

This river is a promise of freshness, especially when it is possible to navigate its waters in the shade of the trees, whose shapes, heights and thicknesses vary depending on the region. Its waters are a source of life: they contain fish that are sometimes sacred in a country with an animist majority, and even hippos and crocodiles.The latter have a discreet presence, as seen in some legends of the Baulé people.

Baulé Mask. National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin

In fact, after having undergone the domination of the Denkyéra – this kingdom exercised its authority over much of what is now southern Ghana – during the 17th century, the Ashanti, under the leadership of Oséi Tutu, organized themselves by founding the city of Kumasi. Having settled north-east of the kingdom of Denkyéra, in 1695 they made Kumasi the centre of a new power. The warlike vocation of the Ashanti kingdom was immediately evident. During Oséi Tutu’s approximately thirty-year reign, several victorious expeditions were undertaken against the Doma, Denkyéra, and Akim kingdoms.Around 1731, after the death of Oséi Tutu, a succession conflict between two of his grandsons, Apoku Waré and Dakon, nearly destroyed the Ashanti kingdom. In the end, the former won and the followers of the defeated pretender migrated westward. Finding the eastern region of present-day Ivory Coast occupied by their Agni cousins, they decided, under the leadership of Queen Abla Poku, to continue westward, until they encountered the Comoé River, which stopped them. But not for long.

This is where legend meets history. The total absence of bridges and the immensity of the river forced the queen to seek the favours of the water gods. After some prayers to the spirits of the river, the sorcerers revealed to the queen that to cross it it was necessary to make a sacrifice. For this, chickens, rams, gold and all the riches that the queen possessed were offered. But the gods did not accept them, since they still asked for more. They asked for something of great importance from the queen… the sacrifice of her only son.

Located on the banks of the forest and savannah, the Baulé people have a history inseparable from the Comoé River, the longest in Ivory Coast at 1,160 kilometres. Filr swm

To save her people, the queen sacrificed her son and suddenly hippos came out in a line on whose backs the queen, her court and her servants passed. The latter, not having the right to attend the sacred ceremonies, did not know of the death of the crown prince. When they noticed his absence on the road, they inquired about him. In response, and according to the current version of this legend, the queen said bauli, meaning “the son is dead”. Hence the name that this people would take, with the modification to baulé made by the French colonizers.

Having no grandchildren, it was Ak’va Boni, the queen’s nephew, who succeeded him around 1760. The Baulé formed a large kingdom around Sakassu, which remained in a centralized form for about 50 years. Until the first half of the 19th century, there was a single throne that exercised absolute authority over all the Baulé. But then this authority weakened and was replaced by that of the leaders of the eight tribes that make up the Baulé nation. (Open Photo: from left: CC BY-SA 4.0/ Mickey Mystique – CC BY-SA 4.0/Isabelle Ferreira Cult – CC0/ Daderot) – (J-A.Y.)