DR.Congo. New tensions between the church and the state.

The Congolese judiciary threatened to prosecute the Archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Ambongo. Such a move has deepened the crisis between the authorities and the Catholic Church to a level unprecedented since Cardinal Malula went into exile

under the Mobutu regime.

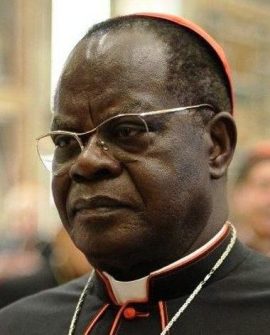

Over the last few weeks, the crisis has been deepening between the government and the Roman Catholic Church. At the end of April, the state prosecutor of Kinshasa ordered an investigation into the country’s senior prelate, the archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo.

In a letter dated April 27, the attorney general of the DR Congo’s court of cassation, Firmin Mvonde Manbu, told the attorney of Kinshasa’s Matete district court that Ambongo’s “seditious remarks” had served to “discourage the soldiers of the republic’s armed forces” and encouraged “the mistreatment of local populations by rebels and other invaders.”

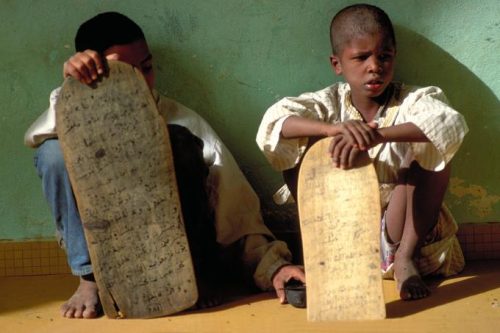

The archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo. He has been a vocal critic of the government’s failure to restore peace in eastern Congo. Photo: José Luis Silván Sen

The anger of the judiciary and of the government was prompted by the cardinal’s homily during the Easter celebration. Alluding to the defection of Congolese politicians to the M23 rebel movement, the archbishop said: “We can call them traitors; they sided with the enemy, but the basic question is, why did these people act in such a way? This is because here we continue to take actions that injure other people, harm the national communion, and exclude other people,” he said.

His statement triggered an angry reaction from government spokesman Patrick Muyaya, who declared that these remarks can be interpreted as “moral support” for the M23 rebels.

In his letter, Mvonde Mambu said the cardinal had declined an invitation to his office on April 25 and accused the bishop of “inciting the people to revolt against official institutions and to attacks against human life.” The letter also warned the Matete attorney that any failure to investigate the cardinal would be considered “an act of complicity with the deeds mentioned.” Such an incident is a further step in the deterioration of relations between the bishop and the state. Relations had already soured in March when the chancery of Mgr Ambongo’s archdiocese accused officials at N’Djili International Airport of “degrading treatment” of the cardinal after he was denied access to the airport’s VIP lounge, allegedly compromising his security.

There is a long tradition of persecution against Roman Catholic priests and their relatives.File swm

Since President Felix Tshisekedi’s first controversial election in 2018, Cardinal Ambongo has been a vocal critic of the government’s failure to restore peace in eastern Congo. He also condemned the December 2023 election which returned Tshisekedi with more than 73 percent of the vote as a “gigantic, organised mess”.

It is no coincidence that the prosecutor who intimidated Ambongo also played a central role in the characterisation of the murder of the former minister and spokesman of Moise Katumbi’s Ensemble pour la République party, Chérubin Okende, as a suicide. The intimidation of the Cardinal appears to be in retaliation for his condemnation on 20 March of the “incomprehensible conclusion” of the investigation into Okende’s murder, despite the fact that the victim’s body was riddled with bullets in his car. At the time, even government spokesman Patrick Muyaya spoke of a murder. Cardinal Ambongo said the prosecutor’s conclusion showed that ‘Congolese justice is really sick’.Two days later, the gap between church and state widened even further when the National Bishops’ Conference of Congo issued a communiqué entitled ‘You will not kill’ in protest at the government’s decision to reinstate the death penalty after more than 20 years by lifting a moratorium on executions. According to the bishops, the desire to get rid of traitors in the army can in no way justify the death penalty.

A long tradition of persecution

There is a long tradition of persecution against Roman Catholic priests and their relatives. In 2012, the nephew of Ambongo’s predecessor, Mgr Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, was shot dead by unidentified assailants in Johannesburg. According to the DIA news agency, the young man was killed in an attempt to steal his mobile phone.

While some said the killing was not unusual given South Africa’s high levels of crime, others suggested that Christian Monsengwo had been deliberately targeted for political reasons, since his uncle Mgr Monsengwo had declared that the results of the 28 November 2011 presidential election, won by Joseph Kabila, were “not in conformity with truth and justice”.

Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya (1939 – 2021) was the Archbishop of Kinshasa from 2007 to 2018.

Seven years later, the Catholic news agency FIDES reported that unknown individuals tried to break into Mgr. Monsengwo’s home on January 30, 2018, again in the context of violence perpetrated against the Roman Catholic Church and its leaders.

During the General Audience of January 24, 2018 in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Francis condemned the violence that occurred on the previous days in the DRC, where the police and security forces clamped down on pro-democracy demonstrators in front of the churches of Kinshasa, killing at least one person on that day. A few days before, the Congolese bishops deplored a campaign of intoxication, disinformation, and defamation waged by the authorities against the Catholic Church after Cardinal Monsengwo condemned the “barbaric” repression of demonstrations on December 31, 2017 in Kinshasa, demanding the organisation of free and fair elections (which should have been held in 2016) before the end 2018. At least 20 people died in the incidents; there were many arbitrary arrests; and church buildings were desecrated. The popular anger was caused by Kabila’s refusal to abide by an agreement brokered by the Roman Catholic Church and signed on December 31, 2016, and by the opposition’s electoral agenda.

A long tradition of resistance

Cardinal Ambongo has followed in the footsteps of his predecessors, who opposed the dictators who ruled the country under the Mobutu regime, the Kabila dynasty and then the poorly elected Tshisekedi. After independence, the Roman Catholic Church took a more conservative stance in the face of the killings of priests and nuns during the Simbas rebellion. But as state structures crumbled under a combination of corruption and bad governance, the social role of the Catholic Church grew, providing education and health services that the state could no longer provide.

Cardinal Joseph Albert Malula (1917 – 1989). He went into voluntary exile in Rome after becoming the target of attacks by Mobutu’s one-party media. Photo: Eman Bonnici

The first serious clash occurred in the early 1970s, when the Archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Joseph-Albert Malula, went into voluntary exile in Rome after becoming the target of attacks by Mobutu’s one-party media. Indeed, Mobutu could not tolerate Malula’s opposition to his new “authenticity” revolution, which consisted not only in renaming the Congo to Zaire, but also in deleting Christian “colonial” names from civil registries.

During Mobutu’s dictatorship, the Roman Catholic hierarchy, spurred on by grassroots communities inspired by liberation theology, began to disseminate calls for freedom and social justice. One of the boldest calls was the book “Chemins de libération” (Ways of Liberation) by the Archbishop of Kananga, Mgr Martin-Léonard Bakole, published in 1978. Another prominent figure was Father José Mpundu, founder of the Amos group, who preached non-violent resistance to human rights violations. The Catholic bishops also forced Mobutu to abandon the one-party state and restore political pluralism in 1990, while Mgr Monsengwo took over the leadership of the National Sovereign Conference to organise the democratic transition.

Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo condemned the December 2023 election as a “gigantic, organised mess”. Photo: Lwanga Kakule

Cardinal Ambongo is the heir to a decades-long tradition of resistance against authoritarian abuses. But at the same time, on 16 May, he showed a certain talent for realpolitik. During a two-hour meeting with Felix Tshisekedi at the presidential palace, in the presence of Mgr Andriy Yevchuk, charge d’affaires of the apostolic nunciature, both sides tried to defuse the tension. Speaking to journalists after the meeting, the Cardinal said that it had been necessary to clarify some points about the legal proceedings against him, which had led to “misunderstandings”. He also said that the Church and the State agreed on one point: “to work for the good of the Congolese people”. (Open Photo: The work of Congolese artist Daniel Gambere)

François Misser