Mission. It’s worth it.

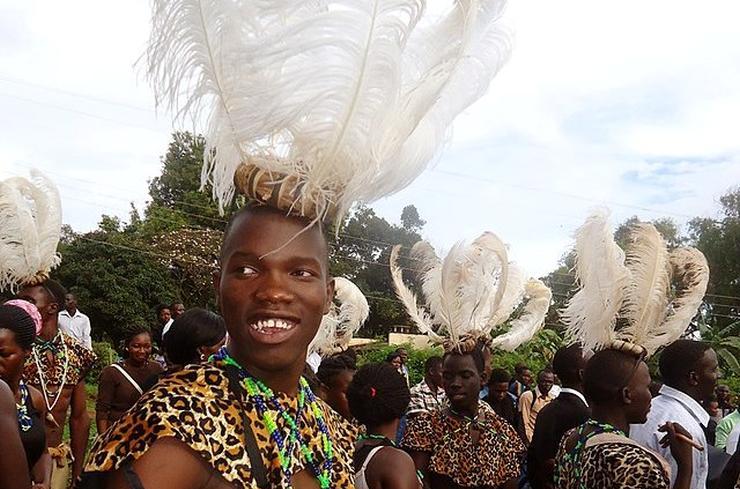

They come from three different continents: Asia, Africa and Latin America. They study theology in Granada Spain. The reason why they chose the mission. Here’s what they told us.

My name is Tran Minh Thong, although my baptismal name is Peter. I was born in Vietnam on All Saints’ Day 1993. I was the youngest of six siblings. Like all families, mine had its wounds, and in the Vietnamese cultural context, being the youngest, I had no say in the decisions

my family made.

When I started high school, my friends and I became addicted to gambling. I spent money, wasted time, neglected my health and got lost in the virtual world. In those years I didn’t care about my future, I only thought about having a good time and being on the Internet. My life had no meaning or motivation.

However, I felt a strange energy, like a voice whispering inside me. I began to participate in the Pro-Life Movement, which defends life from the womb, and also in the charismatic movement. For the first time, I experienced that God is alive and close to me.

One day, praying in a corner of my room, I told him: “I want to offer my life for the Mission in Africa”. It was no coincidence that I met a Comboni missionary, and as I read the missionary testimonies that he sent me, my love for the Mission increased.

Eventually, I entered the Comboni Missionary community in Saigon, Vietnam, where my second life began. It was like finding a life jacket in a rough sea. I was thirsty for an orderly, healthy and courageous life because I was aware that I had thrown a lot of time out the window and had to recover what had been lost.

After several years of formation in the Philippines, I made my first religious profession and consecrated my life to the Lord for the Mission. I arrived in Spain a few months ago, after being assigned to the community of Granada to continue my training. I am discovering this country, its history, its climate, its food and, above all, its people.

The first challenge I have to overcome is the language, which is

not easy for us Asians.

Another challenge is living in an international community with so much to offer but in which I sometimes find myself lost because I am the only Asian. I know it’s part of missionary life and that I will make it eventually. We live in a world that rejects God’s presence, but in which there are still people who seek Him. I believe that the Holy Spirit is constantly at work in the world and in the Church.

Emmanuel Alejandro, “If you want to, talk to him”

I’m Emmanuel Alejandro Majia Sanchez, I’m 31 years old and originally from Magdalena, in the Mexican state of Jalisco. I have always known the Comboni Missionaries because every month they carry out missionary animation activities in my parish, especially accompanying the so-called Comboni Ladies. Despite their advanced age, most of them continue to support and give their best for the Comboni Missionaries.

My mother did not belong to this group, but she always collaborated with the annual campaigns of the Comboni Missionaries. After her passing 21 years ago, my family kept that commitment. The coordinator of the Comboni Ladies, Maria de Jesus Altamiro, was a key person in my decision to enter the Comboni Institute.

In 2014 I entered the diocesan seminary of Guadalajara, but I left the following year. On the way home, my parish priest asked me to help him as a sacristan for a few weeks while I found work, but what was supposed to be a few days turned into four years.

Every time she saw me in the parish, María de Jesús asked me a question that made me uncomfortable: “Are you going to spend your life cleansing the temple?” One day she said to me: “The Comboni Missionary is coming next Friday. If you want, talk to him.”

Even though I replied that I didn’t want to know anything about seminaries or anything like that, I spoke to the missionary, who gave me the biography of Saint Daniele Comboni. I read it and I was impressed by his tenacity; on 18 August 2018, I began my Comboni formation.

On May 13, 2023, I took my first vows and was sent to Granada

to study Theology.

I arrived in Spain on October 5th, when the course had already started at the Faculty of Theology in Granada, so all I could do was unpack my bags and start the lessons. The first week I learned about my apostolic position in the Calor y Café Association, where migrants in irregular situations are helped. After all the road travelled, a mixture of pain and joy, sleepless nights and early mornings, tears and smiles, I can say that missionary life is worth it.

Justin, seeking the will of God

My name is Justin Assey Yao. I was born in 1997 in Grand-Popo (Benin). I am the fourth of a family of five children who grew up in a simple, believing and peaceful family environment. As a child, I left my village to go with my aunt to Gonzagueville, Ivory Coast. I completed my

primary studies there.

In 2009 I received baptism and first communion. That same year I returned to my country, to Benin and precisely to Cotonou, to continue secondary school.

My missionary vocation was born in the ordinary context of my life. At the end of the fifth year of confirmation catechesis, our catechist asked us how we would serve the Church after receiving the sacrament. The question awakened the flame of the Lord in me.

I later joined the group of altar boys in my parish, which strengthened my life of faith and my vocation, and when I had the opportunity to learn about Comboni’s missionary life I was overwhelmed by his missionary zeal, by his love for Christ and his charism of evangelizing Africa despite the difficulties and unreliability of resources.

I decided to become a Comboni missionary the day Comboni Father Leopoldo Adanle was ordained in my parish. I got in touch with the vocation promoter and entered the postulancy in 2016.

In this first stage of formation there was no shortage of difficulties, which I resolved through prayer, the advice of the formators and the support of my brothers in the community. On May 8, 2021, I made my first religious profession and I have been in Granada, Spain for three years to complete my theology studies.

As missionaries we are called to study, observe, dialogue and understand the culture and modus vivendi of the place in which we find ourselves to better integrate and proclaim Christ. In a world where the message of the cross and the spirit of sacrifice proposed by Jesus seem to conflict with the search for individual and material well-being, we must bear witness to Christ, which is why it is worthwhile being missionaries today. Throughout our lives, we must continue to seek the will of God, whose love for us is permanent, even in the midst of our wilderness and vulnerable humanity.

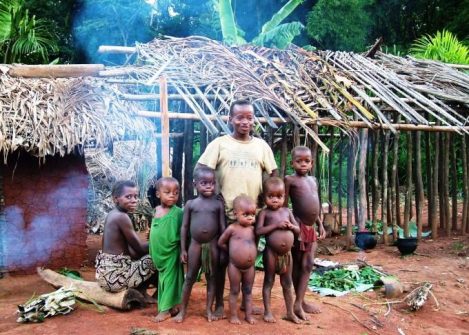

(Photo: From Left: Emmanuel Alejandro, Tran Minh and Justin)