To cope with increasingly recurring droughts and animal deaths, the northern ethnic group, equipped with a solid culture, is changing its habits. Agriculture takes the place of pastoralism, due also to targeted initiatives by the missionaries of Saint Paul.

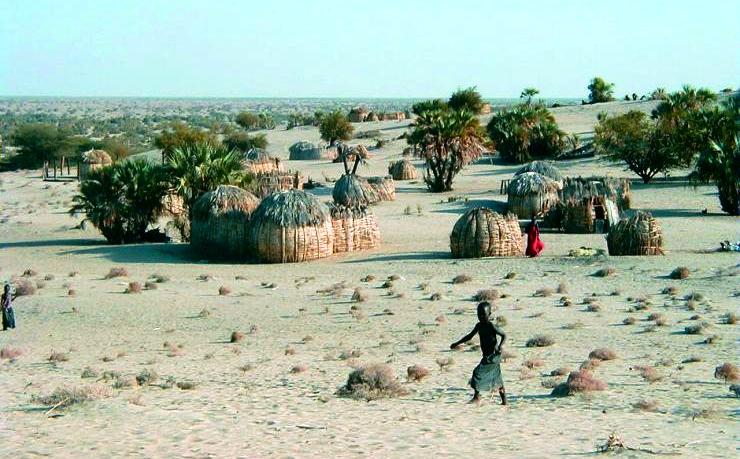

From the rocky hill, the view of the semi-arid plain is of a beauty that is difficult to express in words. It extends endlessly, empty, without any houses or traces left by man, so open and empty that it seems like a sea and not a plain. Behind us, above the hill, the mountains rise, glistening in the hot sun. The rocks appear wet but in reality, it is just the reflection of light on these volcanic stones.

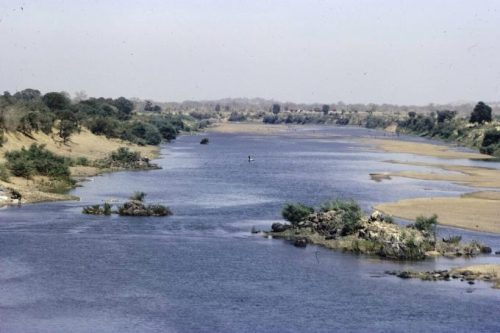

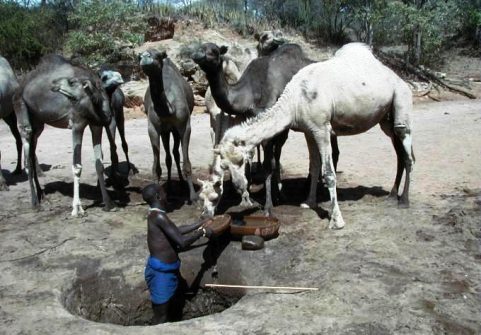

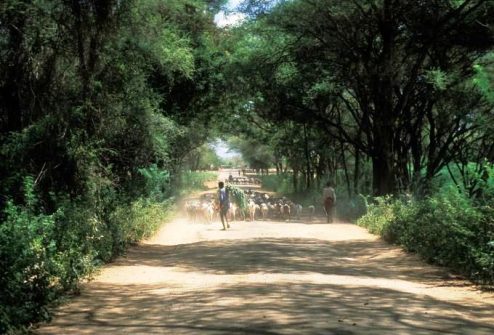

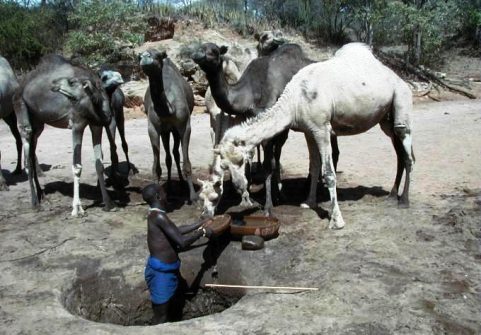

Very little water flows here in northern Turkana. File swm

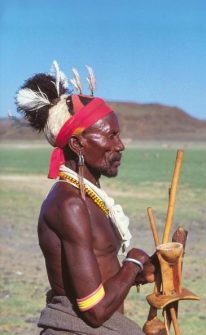

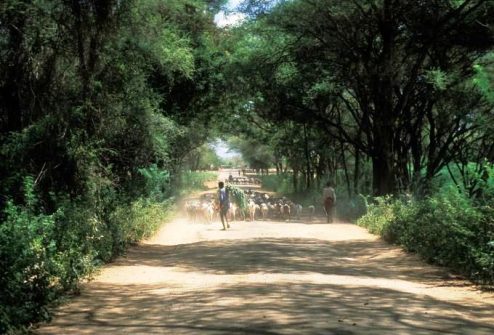

Very little water flows here in northern Turkana where Kenya borders Ethiopia, even though Google Maps tells us that we are in South Sudan. Turkana takes its name from the people who have always inhabited it, a population of semi-nomadic shepherds whose footprint on the territory is small, certainly less invasive than the thousands of red termite mounds that rise like columns. The borders are drawn by the states, but these spaces are continually crossed, following their animals, also by other peoples similar to the Turkana, such as the Nyangatom from the north or the Toposa from the west. Sometimes, they come into conflict when drought hits hard and animals begin to die.

Far from Nairobi

We are in Lobur, one of the headquarters of the missionaries of the Catholic Missionary Community of Saint Paul, of Spanish origin, whose members, mostly African, have various communities scattered in this part of Kenya. Their activities are also a spotlight on the county’s problems. Turkana is very different from the other 47 counties into which the country is divided.

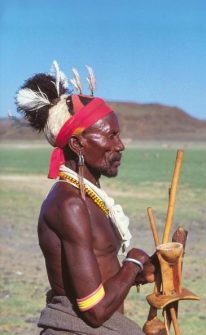

Turkana, a population of semi-nomadic shepherds. File swm

It is an arid land, classified as semi-desert, subject to droughts, which are increasingly recurring due to climate change which is felt here more than anywhere else. The average temperature increased by 2 degrees between 1967 and 2012, and the rainy seasons are getting shorter. Turkana herders usually move two or three times a year during the rainy period (which is in November and from April to June) but the drought that has lasted since 2019 has changed their habits. It is estimated that around 440,000 animals died between then and mid-2022 and that 60% of the population is at food risk. In 2019, again as a result of climate change, there was a massive invasion of locusts from Yemen which depleted the vegetation already severely tested by drought. In Kenya, there are 44 different ethnic groups, each with its own language, but the Turkana people are certainly the most isolated and distant from Nairobi not only from the point of view of distance in kilometres but above all from that of education, health and food security.

Agriculture as the answer to drought

Lobur’s mission offers a small model of how to address the county’s major problems. The first is to find water, which is there, but deep in the ground. At the foot of the hill, there are green spaces where cultivation is carried out using the water extracted through American windmills or through pumps powered by solar panels which also serve to provide electricity given that the territory (like most of the county) has no electricity supply. Small dams are also built at natural collection points which serve to create water reserves. Continuing across the plain, we come across an agricultural farm created with the help of experts from the Israeli Arava Research Institute.

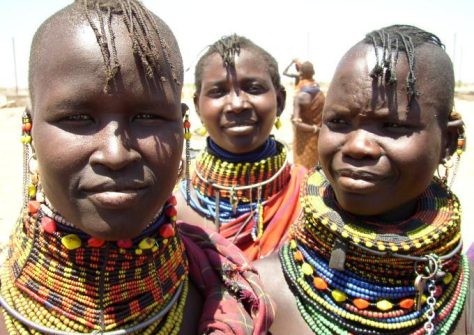

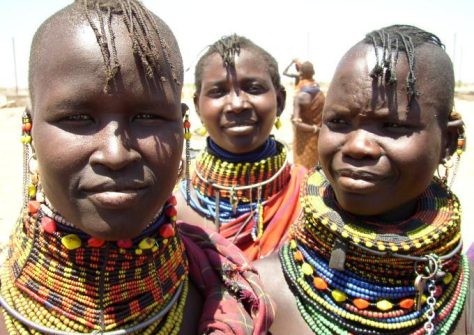

Women are more pragmatic. File swm

Some missionaries had met them in the kibbutzim where they had noticed their ability to cultivate even in areas that were extremely arid. The Furrows in the Desert project includes a training school aimed at aspiring Turkana farmers who within 6 months learn to cultivate even in a place where water is scarce and alkaline, therefore suitable only for certain types of vegetation such as squash, small local pumpkins, watermelons, local species of courgettes and spinach. The transition from pastoralism to agricultural activity is not such an immediate thing for a culture as strong as that of the Turkana. Men tend to reject it, but women understand its importance and step forward to manage large community gardens where water is distributed drop by drop. «We are not asking him to change culture but to introduce innovations such as cultivating the land – missionary Father Joe Githintji explains. During a drought, animals die but agriculture continues to give them food. If they produce, they can sell the vegetables and with the money earned, once the drought ends, they can buy back the livestock. It is virgin land, never cultivated before; they must discover this possibility.”

The Turkana County is an arid land, classified as semi-desert. File swm

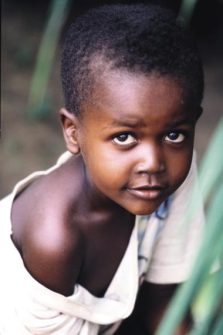

For women, who are more pragmatic, it’s easy. A few kilometres away from there is a primary school run by the mission. Beyond the school, there are vast community gardens cultivated by women who irrigate them with water extracted from pumps powered by the wind. The produce is partly sold and partly cooked for the children who attend school. This is a way to convince families to send their children to school, given that they have at least one good meal a day there. In this way two objectives are achieved: nutrition and education. According to Save the Children, in Turkana, only half of school-age children are enrolled in primary school, well below the national average of 92%, while the adult literacy rate in the county is 20%.

Water, agriculture, education, and health are the services that these missionaries offer and the people, attracted by these opportunities, migrate and form new villages around the missions.

Violence and Conflict

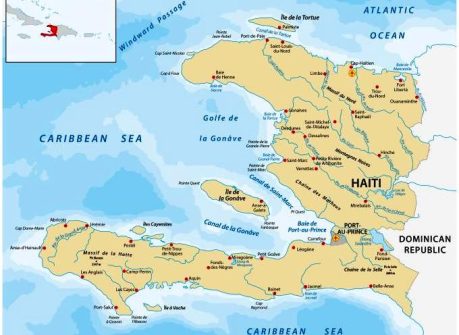

In the far north of Turkana is the region called the Ilemi Triangle, which is a territory claimed by South Sudan. It is one of the many non-demarcated borders in Africa. There are more than a hundred and they must be resolved by 2027 for the African Union. In Kibish, the capital of the area, the missionary community of Saint Paul has its own outpost which it reaches every 10 days.

In these borderlands, there have historically been many conflicts between the Turkana and the Dassenech (Ethiopia), the Toposa (South Sudan) and, further west, the Karimojong (Uganda).

The government supplied semi-nomadic populations with automatic weapons. File swm

The problem worsened when, at the end of the twentieth century,(mostly Kalashnikovs) to defend themselves against theft of animals or attacks and it is quite common to see shepherds leading their livestock with a war rifle instead of a stick. Father Joe Githintji: «Since 2020 we have achieved peace in this territory and there are no more killings, even if further west on the borders of South Sudan there are still difficult situations». When there are criminal acts of this type, the Kenyan government acts quickly: it captures the thieves, punishes them and returns the animals.

The Lake

Lake Turkana, which runs along the entire length of the county to the east, is the largest desert lake in the world. About 250 kilometres long, it has alkaline water, not suitable for humans or even for irrigation. Despite this, the Turkana still drink for want of anything better incurring various physical problems (teeth and bones). In recent years the lake has been subject to contradictory phenomena: the Ethiopian government is building a dam on the Omo River which supplies 90% of the lake.

Once construction is completed, Turkana risks the same fate as the Aral Sea in Central Asia.

Lake Turkana is the largest desert lake in the world. File swm

In fact, however, the opposite phenomenon is taking place: Lake Turkana has expanded by 10% in the last 10 years, covering an area of approximately 800 km² and this is presumably due to the accumulation of sudden rains that do not dissipate. This causes desertification in the interior and floods on the shores of the lake which force the Turkana to abandon their villages and move inland: two opposite phenomena but both expressions of climate change. «The Turkana who live on the lake – claims Patrizia Annibaldi, a lay missionary from the missionary community of San Paolo in Nariokotome – are mostly fishermen and have this advantage over those who live only from sheep farming, but the lack of drinking water is still a serious problem for them.

Adaptability

The shepherd men, the women who look after their children, cook, erect and dismantle the house when they migrate: this is the traditional life of the Turkana. Will it be able to exist in the future or will it be swept away by modernity and climate change? If you ask these questions, the answer you get is always the same: Turkana culture is strong and will resist. «The Turkana belong to Turkana, to their land, not so much to Kenya – claims Peter Bii, a young aspiring missionary from the community in Lobur. They suffer from climate change, but they hope to solve the problem, they don’t want to leave their land.

If drought comes, they move, here the land is free, without owners, they move where there are dams.

They move to where there is water; they move and life continues.File swm

They move to where there is water; they move and life continues. They accept these difficulties, after all their life has always been hard.” However, this cultural solidity also allows change. During our trip, we met many young non-traditional Turkana people, such as Jacinta and Purity, two girls who were good at school and dressed in modern clothes. The community is proud of the new generations who go to school and does not hinder them; on the contrary, it helps them. Once they have finished their studies, they will decide what to do, whether to live in the city or return to their community to help it. Here too, Peter Bii has no doubts: «Even the emancipated prefer to return. Maybe they work for the government but they also work for their people.”

Nicola Rabbi