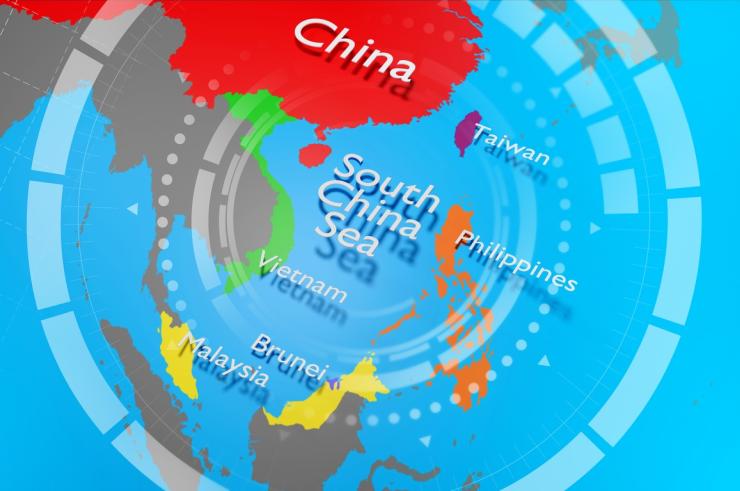

Tensions between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea.

The Navy (PLA Navy) of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has expanded its presence near the Spratly Islands, an archipelago located in the South China Sea, at the centre of bitter territorial disputes.

Although they fall within the exclusive economic zone of the Philippines, China claims sovereignty over these islands and this has caused the emergence of tensions over time.

On 12 July 2016, in line with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the arbitral tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines regarding the dispute over the disputed territories with China, but this did not resolve the issue.

In recent months there have been incidents that are leading to strong tension between the two countries in the area concerned. Among the most serious episodes was the accident on March 5, near the Second Thomas Shoal, a submerged reef in the Spratly Islands.

On that occasion, two collisions were recorded between Chinese Coast Guard ships and their Philippine counterparts, which caused four injuries among the latter.

Subsequently, on May 19, the Chinese Coast Guard attempted to obstruct the medical transport of a member of the Philippine Navy. Furthermore, between May 28 and June 3, the Philippine Navy detected the presence of approximately eleven ships belonging to the Chinese Navy in its exclusive economic zone.

In recent days, Beijing has communicated a possible implementation of the rules on the violation of maritime space, which has caused great concern among workers in the Philippine seafood sector. The new rules, in fact, provide for detention of up to 60 days for foreigners who illegally cross the borders as understood by China.

Regardless, China and the Philippines remain trading partners, which is why Beijing’s recent provocations would seem to be linked more to tension with the United States than to dynamics strictly connected to the relations between the two Asian actors.

The relevance of the South China Sea lies in its rich fishing basin and the presence of oil and natural gas deposits. In particular, its trade route is crucial to the Chinese economy, as 40% of Beijing’s exports pass through these waters. Since 2023, the presence of military ships and the Chinese Coast Guard has increased in the areas near the Second Thomas Shoal to limit the supply missions of the Philippine Navy to the Sierra Madre, a World War II wreck purposely stranded in the shallows in 1999 by the Philippines to assert its own jurisdiction.

In this context, the current President of the Philippines Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr seems to have adopted a less accommodating attitude towards China than his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte. Marcos Jr, in particular, has launched measures aimed at strengthening the control and defence of his territories such as the transparency program with the media and the intensification of the presence of the Coast Guard in the area.

Based on this, the Philippines allowed journalists from the main newspapers access to the disputed area, with the dual aim of raising public awareness of the Navy’s refuelling missions, since in the past the latter were not reported publicly, and document any clashes with Chinese ships in detail. In addition, in the last period, the commitment of the Philippine Coast Guard in escorting some of the missions to the Sierra Madre has been highlighted.

Finally, the Philippine leader sought US support in the framework of the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement of 2014, and in mutual agreement with the US Department of Defence announced the creation of four new military bases in April 2023.

Three of these are planned between the provinces of Isabela and Cagayanuna, in the direction of Taiwan, while the last one will be established on the island of Balabac, near Palawan, a strategic position given its proximity to the Spratly Islands.

Manila and Washington are linked by a Mutual Defence Treaty dating back to 1951. Should an escalation occur in the area, the US State Department has specified that the mutual aid provided for in the event of a foreign attack is also valid for the territories controlled by Philippine Coast Guard, including the Spratly Islands.

The Philippine perspective on regional security emerged a few weeks ago in Marcos Jr’s speech at the latest Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. The President specifically expressed the fear that the states of South-East Asia would become areas of conflict between the superpowers, a concern historically shared by all the countries in the area.

Precisely in this context, the centrality of ASEAN and the negotiations with China for the approval of the code of conduct (COC) aimed at making the South China Sea an area of cooperation and peace

are underlined.

Overall, China seems to want to maintain an assertive type of behaviour, asserting its historical reasons and its superiority in the navigation area. Nonetheless, Manila remains an important trading partner for Beijing, necessary in the supply of raw materials such as nickel and also in the trade of semiconductors, as the country plays an important role in the final part of the microchip production chain.

Both states seem to want a diplomatic resolution and therefore, in the short to medium term, a clash between the two countries appears unlikely. In the short term, a new appeal to UNCLOS by the Philippines cannot be ruled out to guarantee freedom of navigation in its exclusive economic zone and show China’s violation of international law.

Given that Beijing is currently involved in recognizing the authority of international bodies, there is a possibility that it may pause its historical claims in the area. However, the risk of incidents in the area remains rather high and failure to cool tensions between Beijing and Washington could change the current scenario, opening up towards a possible escalation which could also involve the Philippines. (Territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Illustration. istock/Leestat )

Sofia Bertolino/CeSI