Safeguarding the Environment: Costs and Benefits.

“Do we want our children and their children to ask us: ‘Why did your generation destroy our home, when you knew that what you were doing was harmful?’ We would go to great lengths to safeguard them from anybody who would hurt them. So, we also have to protect them from living in a dysfunctional home, a planet where the systems

are no longer working”.

Our home, our Earth is given to us entirely as a gift from God. There is nothing we have done to deserve it or earn it. God has given us a perfectly placed home, with just the right conditions for us to thrive.

We are part of a delicate web of millions of species that support the life of plants, animals and tiny single-celled organisms that are neither plant nor animal. If we remove one of the strands in this web, then the whole system feels the damage. Removing too many species from this web will make irreversible changes that will cause this web of life eventually to break down and stop functioning.

Although scientists have been investigating the heavens for decades and examining other starts (suns) and their solar systems (planets), our Earth is the only place that we can live for sure.

“There is no way we can damage this planet and find another place for the human race to continue to live”. 123rf

Our planet is just the right distance away from our sun so that water can exist in solid, liquid and gas form. We are neither too close to the sun, which would be too hot (steamy), nor too far from the sun, which would be too cold (icy.) This is the miracle of God’s providence for us. Even if there was another planet in just the “sweet spot” in relation to its sun, it would take humans thousands of years to get there with the existing rockets. So, people are right when they say “There is no planet B”. There is no way we can damage this planet and find another place for the human race to continue to live.

Humans (and some people suggest, that intelligent animals) have been able to develop languages and cultures, to communicate and to appreciate and rejoice in the gift of our common home.

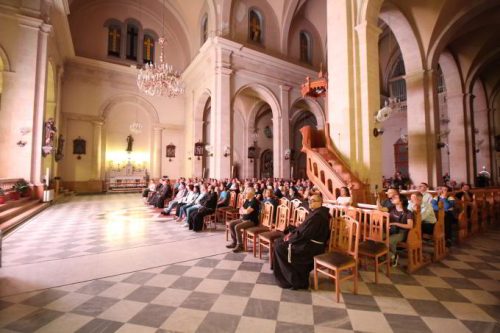

St Francis of Assisi loved the Earth and all of its inhabitants with his entire heart, and he is the model of us of finding joy in everything that surrounds us. The poorest of the poor people, the most distant planet, the lowliest animal, he loved as his brother or sister or mother. When we play, we are appreciating the luxury that we are alive, and that we have time to relax, and are not struggling to survive 24 hours per day. It is a delight to see kids and lambs, and kittens and puppies playing as though they do not have a care in the world, just immersing themselves in the gift of being alive.

Climate change rally. Wikimedia Commons.

Surely all of this is worth preserving – to enjoy now, and to be able to hand it on to our children. There is nothing that we would want to change in God’s plan. Even God looked at Creation on the sixth day, and saw that ‘indeed it was very good’. (Gen 1:31)

We need to protect this delicate balance from people who would just take, take, take everything for their own profit, accumulating more than they can possibly ever use in a life-time. They cut down the forests, sell the animals, make charcoal, drive heavy polluting vehicles, pollute the water, land and air, put concrete wherever there should be natural environment. Thirty years ago, at the “First African Synod”, African bishops discussed how our scarce resources are being tragically mismanaged. In his exhortation ‘Ecclesia in Africa’, after this synod, Pope John Paul II wrote about waste and embezzlement of our common patrimony by citizens lacking in public spirit and about government officials who profit from our countries, and send the money

to foreign bank accounts.

Climate demonstration organized by Fridays For Future in Stockholm. CC BY 4.0/Frankie Fouganthin

Often, we think that they are the heroes of development, the ‘big men’ (and women) making Africa ‘advanced’. But in fact, they are mostly imitating the unsustainable models of the industrialised countries, which are now in trouble because of global warming, and drowning in their own waste. Do we want to go down the same destructive path to have our “moment in the sun” and then leave others to undo the damage for centuries afterwards? Do we want our children and their children to ask us: “Why did your generation destroy our home, when you knew that what you were doing was harmful?” We would go to great lengths to safeguard them from anybody who would hurt them.

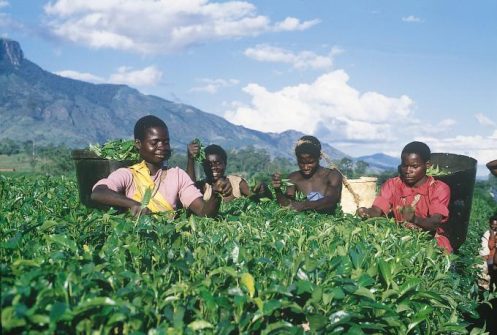

So, we also have to protect them from living in a dysfunctional home, a planet where the systems are no longer working. What price are we prepared to pay to keep our home in order? Even if we don’t have children, the world is God’s gift of love to all of us – to all creatures. Are we going to leave it unharmed for all of creation to enjoy? Are we going to leave as small a footprint as possible on the planet when we are finally called to account for how we have enjoyed God’s loving gift? (Open Photo: iStock/amriphoto)

Peter Knox