Music. Apple Music’s list no African artists.

Apple Music’s latest list of the 100 greatest albums of all time has excluded any contributions from Africa. The musical richness of the continent continues has been ignored.

The exclusion of African music from Apple Music’s recent list of the 100 best albums of all time is disconcerting but at the same time not a real surprise. However, the probable reasons behind this omission are discouraging. Africa is still perceived musically as an unknown territory that more often than not arouses consternation, if not a lack of interest. Apple Music has simply chosen to ignore the reviled continent with its endless array of A-list musicians. Like the vast continent, the African musical tradition is equally heterogeneous, changing a lot based on the historical periods and regions of origin.

It is not always easy to find your way around this variety. Look at Kendrick Lamar. When the American hip-hop superstar was chosen to oversee the soundtrack of the Afrofuturist-themed Hollywood blockbuster Black Panther, he basically limited himself to randomly choosing a group of artists mostly from the southern regions of the continent, South Africa in particular.

The DNA of jazz, blues and his own rap can be traced back to Africa, and how their roots are deeply rooted in the continent’s musical panorama.123rf

The Afropop singer Sjava, the queen of Gqom music Babes Wodumo and the rapper Saudi were then selected. From the experience of Black Panther, it clearly emerges that the rapper had no idea how to bring artists from the continent together organically. His selection ended up giving life to a fragmented and above all poorly representative ensemble of the enormous musical richness of the region. Illuminating, in this sense, is an exchange published online some time ago between Lamar and the jazz musician and super producer Quincy Jones, the mind behind Michael Jackson’s trilogy of masterpieces composed of Off the Wall, Thriller and Bad. During the aforementioned conversation, Jones gives the rap star a lesson in African music, assuring him how the DNA of jazz, blues and his own rap can be traced back to Africa, and how their roots are deeply rooted in the continent’s musical panorama. Lamar, in response, appears completely incredulous and not at all sure what to do with all the knowledge Jones instilled. In short, despite the great cultural connection that exists between America and Africa, confusion still reigns supreme.

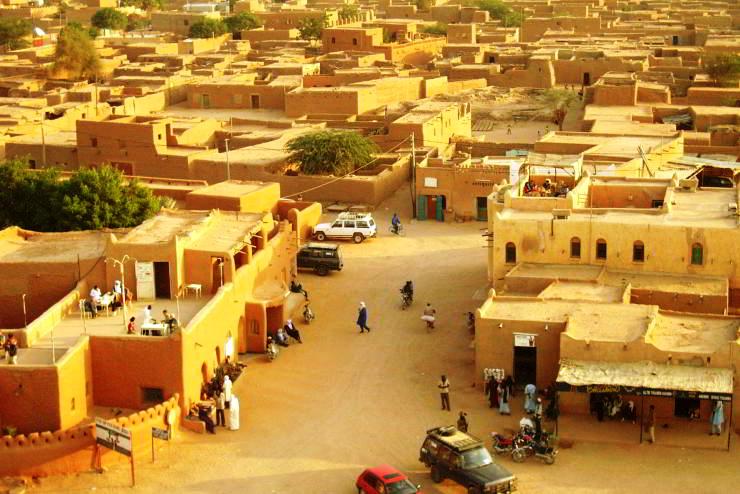

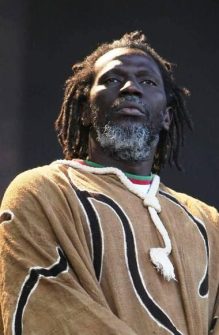

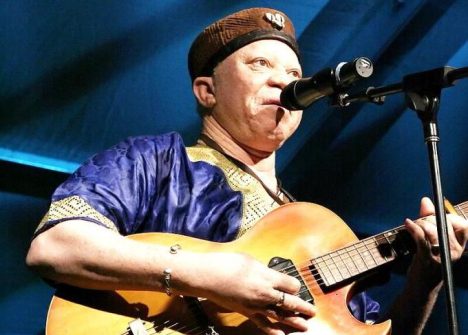

Salif Keïta is a Malian singer-songwriter, referred to as the “Golden Voice of Africa”. CC BY 2.0/ John Leeson

Another great opportunity to showcase the complexity of Africa’s musical heritage has been lost. In fact, each of the regions of the continent is home to incredibly varied musical traditions and genres:

just naming them makes you dizzy.

Only in Mali, the land of burning blues, do we find Ali Farka Touré, Oumou Sangaré, Salif Keita and the incomparable Toumani Diabaté. Their hymn to mystery, the dignity and value of the creative majesty of the Malian soul deserve to be known. Unfortunately, in the West, there are very few circles that recognize and appreciate the greatness of these artists. Obviously, Aya Nakamura also deserves a special mention, a Malian-born singer based in France who has been churning out global hits for some time now.

Discord

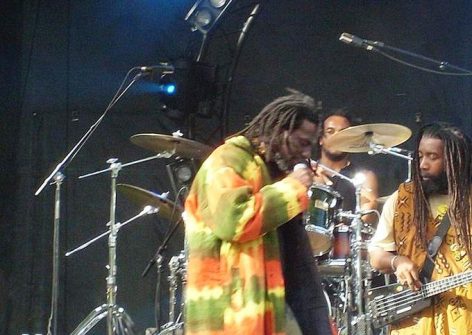

Often however, what is celebrated in the West is not what is popular in Africa, and vice versa. For example, the South African a cappella group Ladysmith Black Mambazo, winner of Grammy Awards and constantly on tour in the USA and Great Britain, is respected at home but is certainly not considered as one of the most avant-garde groups. And the same can be said of the flautist Wouter Kellerman, also a winner of several Grammys. The artist’s trajectory started from abroad and then arrived home: first, his non-South African fans came, and then he started to be appreciated in his own area too.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo is a South African male choral group singing in the local vocal styles of isicathamiya and mbube. CC BY 2.0/ Raph_PH

Artists like the ones just mentioned are in a certain way a cause of embarrassment for the South African public, who don’t really know what to do with them. The impression then is that Western critics and opinion leaders have their own preconceived idea of what African music should be. Everything that is outside this imagery is usually simply ignored, while those who enter it end up enjoying a certain recognition.

In South Africa, rock/pop bands such as Prime Circle, Parlotones, Jeremy Loops and Beatenberg have thriving careers, which also involve extensive touring outside the country’s borders.

As well as the alternative rap duo Die Antwoord, at least until their recent social oblivion. A success that does not, however, translate into greater consideration from critics. Examples of a misalignment as to how artists are received at home and abroad.

From Johannesburg to Cape Town

After all, the South African scene is truly complex and we understand the difficulty encountered by non-local markets in accommodating all this variety. The country’s musical reality is not only divided into different genres but is also fragmented along regional and ethnic lines. Cape Town’s rap scene is very different to that found in Johannesburg or the North-West Province. Modern and traditional genres then present further specificities and differences.

Tyla Laura Seethal as Tyla, is a South African singer and songwriter. The “Queen of Popiano.” CC BY 3.0/ Condé Nast.

Popular styles such as maskandi, mbaqanga and iscathamiya sit alongside jazz, gospel, neo-soul and hip-hop. Each of these variations has its enthusiastic fan base, its awards and its recognitions. Even the amapiano, the last great “export” product of South African music, can count on a pool of events, publications and blogs aimed at its diffusion. Ultimately, each genre relies on its systems and networks to take root in the territory. It’s easier now to understand how complex and multifaceted the South African music scene is. And we are referring here to only one of the 55 countries in the region.

Each of these, in turn, presents a musical scene that changes in heterogeneity and complexity. It almost seems that for the West all this is too much and that it is therefore more convenient to ignore a large part of all this musical wealth.

At the top

There ought to be some exceptions. The global rise of Afrobeats led to the creation of an “African music” category at the Grammys. Billboard magazine, which publishes relaunched charts all over the world, also seems to be following the same path.

The vast majority of the big names in Afrobeats are at the height of their careers, with tours followed all over the world: this is the case, among others, of Burna Boy, Wizkid, Davido, Asake, Rema, Omah Lay, Olamide, Sarkodie, Stone Bwoy, Shatta Wale, Flavour, Tiwa Savage, Yemi Alade, Ayra Starr, Tems and Adekunle Gold.

The exclusion of African albums from Apple’s list is probably the result of a combination of different factors: political, racial or simply ignorance. 123rf

From these extensive forays into the European and American music scenes, much infrastructure is developed, further networks are created and more and more inroads are made. Burna Boy can fill entire European stadiums and people like Davido, Wizkid and Asake prove that they are no different. Afrobeats and amapiano are fresh and popular genres. They manage to cross several dividing lines transversely. Afrobeats artists are increasingly gaining a place in other geographical spaces, collaborating on hits around the world with European, US, Caribbean and Latin American artists. Musicians from other regions find the style, native to Nigeria, simply irresistible, characterized as it is by infectious rhythms, joyful inspirations and profound sensibilities.

Ultimately, it can be said that the exclusion of African albums from Apple’s list is probably the result of a combination of different factors: political, racial or simply ignorance.

What is certain is that this is a mistake, with significant consequences for the continent’s industry. (Open Photo:123rf)

Sanya Osha