Cambodia. Giving Dignity.

The Catholic Church is addressing the social challenges of Sihanoukville. In the face of the human trafficking crisis and social injustice, the response is both spiritual and humanitarian.

Over the years, the port city of Sihanoukville, located on the southern coast of eastern Cambodia, has become a crossroads of various social and political issues. At the heart of these challenges is the human trafficking crisis, which includes prostitution, online scams and violence against Cambodian sailors.

Founded in 1960 by Prince Sihanouk to give Cambodia back a deep-water port and a seaside resort, the city, a symbol of freedom, is now faced with the scourges of modern slavery that threaten its sovereignty. Faced with this alarming situation, which affects not only the trapped foreigners but also the local Cambodian population, the Catholic Church, through various committed actors, is providing a response based on solidarity, justice and human dignity.

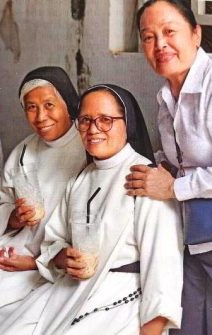

The Good Shepherd Sisters are at the forefront of providing support to victims of Human trafficking. MEP

Sister Michelle and the Good Shepherd Sisters play a vital role in the fight against prostitution and the exploitation of women, while Caritas Cambodia is involved in the issue of online scams and other Church initiatives within the Stella Maris network, aiming to warn the public about violence against Cambodian sailors.The city of Sihanoukville, with its growing attraction to tourists, has unfortunately seen an increase in prostitution and human trafficking. This crisis particularly affects young girls and vulnerable women, who are often manipulated or forced into prostitution by criminal organizations.

Sister Michelle and the Good Shepherd Sisters are at the forefront of providing support to victims of this trafficking. Their work mainly consists of providing shelter to women victims of violence and exploitation in the red-light district of Phnom Khiev, also known as Blue Mountain. Through their shelter, they offer them a safe space in which to rebuild their lives and provide education for their children, as well as vocational training opportunities for themselves. The nuns also provide legal support to victims, helping them regain their dignity and free themselves from trafficking networks.

But beyond the material aspect, Sister Michelle and her fellow nuns, with their many years of experience in a similar context in Pattaya, Thailand, are committed to giving spiritual hope to the women they accompany, transmitting to them the love of Christ and the strength of a faith that helps them overcome suffering and look forward to a different future.

Sihanoukville. The city, with its growing attraction to tourists, has unfortunately seen an increase in prostitution and human trafficking. Shutterstock/Assa2215

Online scams are another serious scourge that affects Cambodia. These scams, often perpetrated by international criminal groups, exploit the naivety of victims by luring them into financial traps, promising fictitious jobs or earning opportunities. Driven by poverty or hyperinflation, as in the case of Sri Lanka, India and Indonesia, victims find themselves in situations of extreme vulnerability.

Caritas Cambodia, in collaboration with local authorities and other non-governmental organizations, offers support to people who have fallen victim to these scams. In addition to providing information and promoting awareness campaigns to prevent scams, Caritas offers support to victims, helping them to recover their funds and rebuild their lives after suffering financial abuse. The Ta Khmau shelter offers an alternative to detention centres, where abuse is common, allowing many victims to avoid it.

Caritas’ approach also focuses on promoting justice and integrity, in a spirit of Christian solidarity that goes beyond material aid. For example, the local Church has joined forces with Caritas to bring together staff from the Ministry of Social Affairs and local NGOs to train them to address the new online trafficking crisis that is rocking the Cambodia-Thailand border in Koh Kong.

A final group of people often forgotten in this new form of modern-day slavery is the Cambodian sailors, often from rural areas: they are among the most vulnerable workers in the Sihanoukville region.

Promises of work on fishing boats attract many, but then find themselves subjected to inhumane conditions and exploitation. The violence suffered by Cambodian migrant workers on Thai fishing boats is effectively depicted in Buoyancy, a Khmer feature film that was a great success when it was screened in 2022.

Fishing boats in the port of Sihanoukville. Within the Stella Maris network, to warn the public about violence against Cambodian seafarers. Shutterstock/Gaston Piccinetti

Often, their working conditions are similar to a modern form of slavery, with many sailors being kidnapped and forced to work on fishing boats off the coast of Thailand, in conditions of extreme violence and deprivation that can even lead to their death.

The Catholic Church, through the Stella Maris network, is working to denounce this exploitation and find solutions.

This year, the local Church has launched a campaign to raise awareness and warn young Cambodians about the dangers of working at sea and to create support groups to assist sailors who manage to return from these dramatic situations.The situation in Sihanoukville is emblematic of the many global challenges to which the Catholic Church responds with humanity, solidarity and faith.

Through the initiatives of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, Caritas Cambodia and the Stella Maris network, the Church is trying to find concrete solutions to the many forms of exploitation to which vulnerable people are subjected in the region.

In this complex context, the mission of the Church is not limited to the distribution of material aid, but is also a testimony of hope and human dignity, faithful to its mission to protect the weakest and defend the rights of the oppressed. (Open Photo: Sihanoukville Downtown. 123rf)

Will Conquer/MEP