Angie Torres. A refugee among refugees.

Forced to flee Colombia, she has managed to rebuild her life in Ecuador. Now she defends the human rights of migrants and in particular of women, who often suffer violence and have fewer opportunities.

Some stories keep hope alive, especially when, despite enormous initial difficulties, they reveal the possibility of significant changes that alter the lives of their protagonists forever. One of these stories is that

of Angie Torres Angulo.

She was only 15 years old when she was forced to leave her home in Colombia, due to the armed conflict that was spreading in the country: her city had been declared one of the most dangerous, and the only way to escape the violence was to leave. Having arrived in Ecuador with her family, she managed to find refuge and make a new start to her life, albeit with many difficulties. One meeting, in particular, represented the decisive turning point that moved the young woman to commit herself to help others and defending the human rights of the most vulnerable.

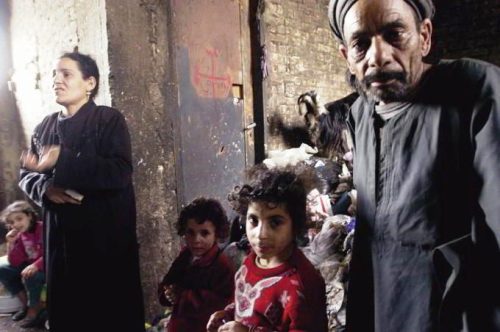

“I met a mother with her children, the father was not with them – says Angie -. They made the same journey as I did, crossing the border between Colombia and Ecuador. It was very difficult for her at the beginning: she had to find a job and, in the meantime, take care of her children, since they were still too young to go to school. She lived in an unsafe place, subject to violence and with poor sanitary conditions. Her house was flooded every time it rained. She needed help.”

It is therefore starting from the testimony of this mother that Torres felt for the first time the need to do something to support those who, like her, had lost their homes and had been forced to leave their homelands, facing an uncertain fate. “This situation moved me to want to fight for them. I wanted to help people move forward.”

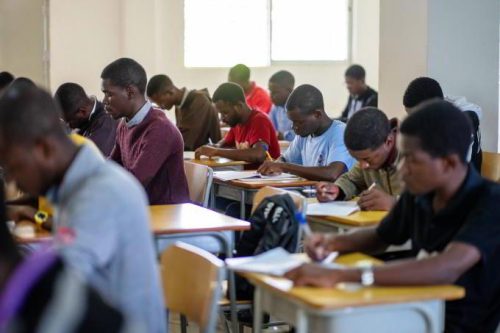

Angie has lived in Ecuador with her family for eight years. For her too, it wasn’t easy at the beginning: it took two years before she was granted refugee status. “As an asylum seeker I didn’t have many rights, such as the right to education or a job that guaranteed an acceptable salary,”

she recalls.

For a year she tried to gain access to school, but it was only thanks to the help of some organizations that she managed to resume her studies and this year she graduated in Forestry Engineering. She is convinced that caring for the environment is also a fundamental element for migration issues: the impact of climate change has a great influence on migration both in the countries of origin and in those of arrival.

But education was not the only challenge he had to face: the relationship with the local community also proved to be rather difficult. Although the cultures of the two countries are very similar, discrimination against Colombians is very deep-rooted. “I have often been the victim of acts of violence, sometimes I had to imitate the local way of speaking to be treated fairly in public places,” said the young woman.

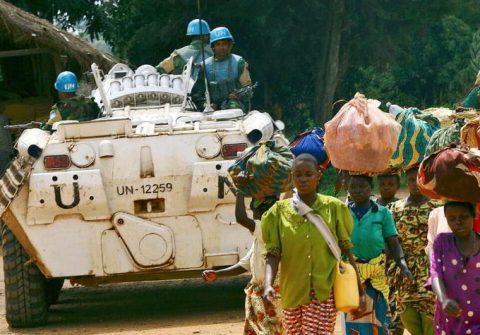

Ecuador is a country where a large number of immigrants periodically converge; in fact, many people from neighbouring states take refuge there due to conflicts and other situations of violence and suffering. For this reason, there are many NGOs present in the area, including the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) which plays a fundamental role. Precisely thanks to this organization and its courses in citizenship, Torres was able to inform herself about the conditions of refugees: “I learned a lot about issues such as discrimination, the culture of peace, interculturalism, new forms of machismo and more generally about human rights. With these tools and this awareness, I can mobilise on behalf of those in need.”

So, Angie today dedicates a lot of time to raising people’s awareness of the rights of migrants, especially those of women and girls, through specific campaigns and seminars in schools. She is also working to create support paths for women who have survived episodes of gender violence. All the activities she organizes are designed for both the Ecuadorian and refugee communities.

By working together, the relationship with the local population has also improved: “We have discovered that there are many more things that unite us than those that differentiate us.”

The focus on gender issues in the context of migration arises from a need that Torres has experienced firsthand: “As women, in my opinion, we are much more subject to the violation of our rights, both in the country of departure and in the country of arrival – explains Angie -. When we arrive in the host country, we often suffer double discrimination: as women and as foreigners.”

“I think we should first of all make our rights visible because even if they already exist, many of us are not aware of them. Then we should exercise them and strengthen them – insists Torres -. If we are aware of them and value them, we can fight for them and make sure they are observed. We can demand respect for them when we feel that they are being violated and be involved in the various decision-making processes to exercise them and make them visible.”

On the rights of migrant women, in particular, she maintains that “a principle of equality must be established, which guarantees equal conditions and job opportunities, and for this to happen gender stereotypes must be eradicated in many contexts and places. This fight becomes even more important given that, as refugees, the discrimination we suffer is greater.”

Angie concluded: “Let’s not give up, let’s keep fighting, and in small steps, we will achieve big changes. Revolutions are built by walking side by side.” (Rebecca Molteni/MM)