Madagascar. The mission with the monk’s habit.

How can a monk be “missionary” if, by vocation, he is called to withdraw from the world and therefore is not in direct contact with the population? Father Christophe Vuillaume, a Benedictine of the Mahitsy monastery in Madagascar, answers.

In a precise sense, the two terms “monk” and “missionary” seem to contradict each other. But the mission is not limited to teaching, the celebration of the sacraments or pastoral initiatives of all kinds, in which the monks obviously do not participate or rarely participate. Perhaps we should ask ourselves: in what sense can the monastic community take its place in the mission of the Church? As the Second Vatican Council clearly understood, the monastery must first of all be what it is, and this is what the local Church asks of us. Because being monks in truth is already

a form of “mission”.

“The monastery must be a spiritual centre for everyone, in search of God”. Facebook

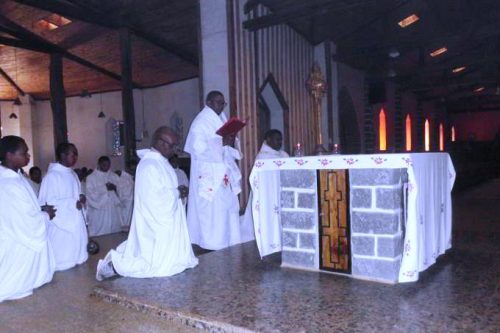

If the monastic community is faithful to its call to seek God in prayer, silence and solitude, but also in fraternal communion, work and sharing, it will in itself be a luminous focus of evangelical life. This applies not only to those who come to the monastery on a daily basis: the poor, the neighbours, the workers, but also to those who come to celebrate the Sunday Eucharist – some of whom do not hesitate to travel 60 km to do so – for the guests and retreatants that Saint Benedict asks us to welcome “like Christ” to benefit from the silence and atmosphere of prayer, but also to receive spiritual teaching, personal advice or even the sacrament of reconciliation. In this sense, as the Council teaches, the monastery must be a spiritual centre for everyone, Christians and non-Christians, in search of God, who perhaps they do not yet know.

Apostle monks

We received an intuition from Father Jean-Baptiste Muard (1809-1854), founder of the Abbey of La Pierre-qui-Vire, our motherhouse. Inspired by his patron, the Baptist, he realized that only the “apostle monks” could work on the new evangelization of France. To do so, he had to send a strong signal to the people: that of a life entirely dedicated to God in the radical following of Christ, as understood by the monastic tradition.His intuition could be summed up in these words: “Make a sign first of all with your life”.

“No other purpose than to “seek God”, in the words of Saint Benedict”. Facebook

Therefore, contrary to what one might think, anchorism, this “distance” from the world, which is essential for the monastic vocation, is also what allows the community to give a strong and radical testimony and, in doing so, to exercise a certain attraction on those who live “in the hearts of the people”. In fact, in the radical nature of their choices, expressed in the practice of the three monastic vows: obedience, the conversion of customs – which include poverty and chastity – and stability, the monks bear witness to the absoluteness of the Kingdom of God. In fact, this is the only justification that Jesus gave for consecrated celibacy: in view (or for love) of the kingdom of heaven (Mt 19.12).Visitors to the monastery often wonder: why do these men and women, who could have done anything else, freely decide to spend their entire lives away from the world, with no other purpose than to “seek God”, in the words of Saint Benedict? This question is already healthy in itself. It will silently make its way into the hearts of every man and woman of good will, especially young people who question the meaning of their life.

The apostolate of prayer

The monk or nun also learns to live ever more deeply what is called the “apostolate of prayer”, uniting every day, in the gift of self and in personal or common prayer, with brothers and sisters who work in the world. A mysterious reality, but a reality. For this to be true, the monk must obviously be as authentic as possible in his vocation. In our so-called “recent mission” countries, this authenticity is going through a delicate phase in all forms of religious life. The values transmitted by the founders must be recognized as such before they can be adopted and embodied by brothers and sisters whose culture is still far from fully embracing the ideals of the Gospel.

“The monks bear witness to the absoluteness of the Kingdom of God”. Facebook

The last transmitters of the charism, coming from Europe, are sometimes disconcerted by the apparent withdrawal from the values they believed they had transmitted with all their heart and above all by living them firsthand. But is it a real retreat, or the testing, but necessary and always purifying, process of authentic inculturation? Honest and rigorous discernment is needed here. It is the whole task of an intelligent understanding of Tradition that transmitters must carry out “to enable those who follow them to inherit not the practices, but the values which they themselves will have to embody where they are, in their time, before transmitting them to others in their turn”. But how can we give to others what we have not received and assimilated ourselves?

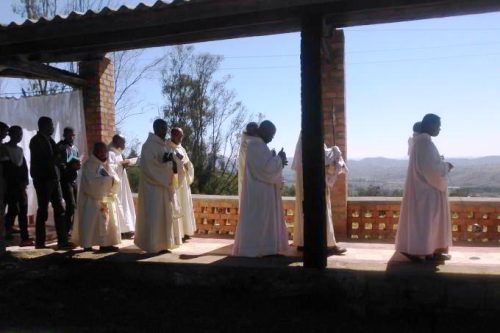

Particular aspects of monastic life in Madagascar

The liturgy. Father Gilles Gaide, a monk from Mahitsy, was one of the main protagonists of the inculturation with his team Ankalazao ny Tompo (“Praise the Lord”). This led not only to the composition of a Malagasy “prayer for the present time”: Vavaka isan’andro, but also to a considerable repertoire of hymns and canticles known almost by heart and widely used throughout the island, even in parishes. While using this collection on some occasions, the monastic communities each composed their own prayer book, according to their own traditions. Today, some continue to recite some offices in French, while others celebrate the entire liturgy in Malagasy.

“We live in Madagascar at a crucial time when our vocation to “seek God” in monastic life will have to be fully expressed, in and through the local culture”. Facebook

Formation. In the 2000s a great effort was made to create a monastic studium, common to our six monasteries and the Poor Clares. After a period of hiatus, it was recently relaunched. Several monks and nuns teach there, as well as some seminary professors. Mahitsy Monastery has been fortunate to have been able to maintain its own theology studium since the 1990s. Some brothers are sent to study in France and at the Catholic Institute of Madagascar.

Integration into the local Church. In Madagascar, we are certainly more aware of this connection than in Europe. This is demonstrated by our mutual participation in some diocesan celebrations or meetings and the cordial relationship with our pastors, who usually understand and respect our monastic charism. Our guesthouses are well frequented, especially on the occasion of the main liturgical celebrations. Also noteworthy is the existence of an assembly of the island’s monastic superiors, which is held every year and which, in addition to exchanges between leaders, includes a training period. A final point to mention is the temptation of an insular population to the detriment of fruitful exchanges and therefore cultural and economic progress. On the other hand, the stay of some brothers and sisters in our French monasteries for study purposes or to complete their monastic training, as well as the sessions organised in Europe, are helping to change things.

“Make a sign first of all with your life”. Facebook

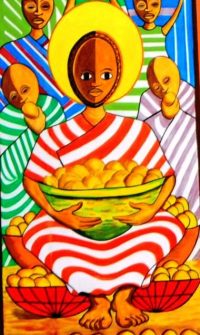

The seed thrown into the soil

We live in Madagascar at a crucial time when our vocation to “seek God” in monastic life will have to be fully expressed, and undoubtedly also enriched, in and through the local culture. The most precise image of this mysterious process is that of the seed thrown into the earth. Fertilised by a soil unique in its characteristics, the plant that germinates, then produces its flower and, finally, its fruit will be at the same time similar to the seed, of the same nature, and legitimately different, marked by its specific components. It is a natural law desired by the Creator to give rise to an infinite number of varieties, not only of shapes and colours, one more beautiful than the other, but also of flavours, aromas and qualities of infinite richness. In reality, this surprising metamorphosis takes us back to the heart of the Paschal Mystery, because nothing about this birth, which will ultimately give glory to God and save the world, can happen if the grain does not die first. (swm)