Tibet. Two Dalai Lamas.

The succession of the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism involves the search for his reincarnation. The current Dalai Lama was indicated in 1937. Beijing wants to have its say on the next leader, but the religious authorities (in exile) are not on board. The possible geopolitical implications.

Amdo region, in north-eastern Tibet. It is 1937, and little Lhamo Dondrub is approximately two years old. A group of monks led by the lama Kewatsang Rinpoche asks for hospitality in Lhamo family’s house. Shortly afterwards, the announcement: Lhamo is the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. The monks pay a large ransom to Ma Lin, governor of the region on behalf of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang, and take the child to the Tibetan capital of Lhasa. Two years later, Lhamo was officially “crowned” the XIV Dalai Lama. From then on, he will be known as Tenzin Gyatso, literally “ocean of wisdom”. Almost 90 years have passed since the journey of those monks. 74 have passed since, in 1950, the troops of Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China arrived in Tibet after defeating the Kuomintang in the civil war. Again: 65 years have passed since that March 1959 in which Tenzin Gyatso left Tibet forever, fleeing to India after the repression of the Lhasa revolt.

Himalayas, on the southern rim of the Tibetan plateau. CC BY 3.0/ Dan-500px

Soon, the time may come when a new boy or girl will be identified as the 15th Dalai Lama. Indeed, in all likelihood, all this could happen twice.

On one side a group of monks, or Tenzin Gyatso himself, on the other the Chinese Communist Party: the boys or girls whose lives will change forever seem destined to be two.

One appointed by the Tibetan spiritual or political authorities in exile, and one by those in Beijing. Result: two Dalai Lamas.

The scenario is imminent, barring agreements which at the moment appear unlikely. Historically, when a Dalai Lama dies, a council of high lamas is formed to seek his reincarnation. In the selection process, known as the “golden urn”, the council consults various signs and oracles, as well as the writings and teachings of the Dalai Lama himself, to be guided in the search which usually ends with the identification of a child born around the time of the predecessor’s death.

Dalai Lama during the Long Life Prayer at the Main Tibetan Temple in Dhramasala. India. Photo: Tenzin Choejot/OHHDL

Once a potential reincarnation has been identified, the child is presented with a series of objects that belonged to the previous Dalai Lama and is asked to identify which ones belong to him. If the child passes the test, definitive confirmation from a political authority is then required.

And here comes the problem. Beijing claims it must certify the choice of the next Dalai Lama, as it has done in the past. A legacy inherited from the time of the imperial era until the beginning of the last century, when Tibet was governed by the Qing dynasty. A legacy that Tenzin Gyatso does not seem willing to recognize.

Also from this perspective, the separation of spiritual authority from political authority was carried out, when in 2011 the Dalai Lama resigned as head of the Tibetan government in favor of a successor elected by the Parliament in exile. It could, therefore, be this entity, not recognized by Beijing which considers it “illegal”, to certify the choice of the next Dalai Lama. At least the one indicated by the exiled Tibetan authorities. The Communist Party could respond with another name.

The ‘Vice Dalai Lama’

The signs of what could happen have been there since 1995, when a 6-year-old boy, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, was chosen as the new Panchen Lama, the second most important figure of Tibetan Buddhism. Three days later he was taken into custody by the Chinese authorities and replaced with another candidate, Gyaincain Norbu. Since then, little Gedhun’s fate has remained uncertain. In 2022, on the 33rd anniversary of his birth, the US State Department reiterated its call for Beijing to “account for the whereabouts and well-being” of Gedhun.

Yet another clarification, if it were needed, is that the US will side with the Tibetan authorities in exile at the crucial moment of choosing

the next Dalai Lama.

Tibet. Lhasa. Young monks practicing the art of debate in a sunny courtyard of Sera Monastery. Shutterstock/Tatiana kashko

In the same 2022 statement, the State Department stated in black and white that Washington supports “the religious freedom of Tibetans and their unique religious, cultural and linguistic identity, including the right of Tibetans to choose, educate and venerate their own leaders, such as the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, according to their own beliefs and without government interference.” Not to mention that, in 2020, the then head of the Tibetan government in exile was invited to Washington for the first time by the Trump administration. A political, as well as spiritual, recognition that had infuriated Beijing and made new turbulence on the Tibetan dossier appear on the horizon.

From Mongolia the one in third position

Another preview of what may happen in the near future came in March 2023, when the appointment of the tenth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa, the third position of Tibetan Buddhism, emerged. He is an eight-year-old boy from Mongolia. The news was greeted with mixed feelings in Mongolia: joy for the choice of one of their compatriots, and fear of China’s reaction. In 2016, the Mongolian government received strong complaints from Beijing over the visit of the Dalai Lama, which, not surprisingly, was the last in the country. The new Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa, heir to the Altannar family (one of the most influential in Mongolia) was also born in the United States. There are those who could read a subtle (geo)political message in it.

The 10th Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa making the Mandala offering to H.H. the Dalai Lama on March 8, 2023. Photo: Tenzin Choejor/ OHHDL

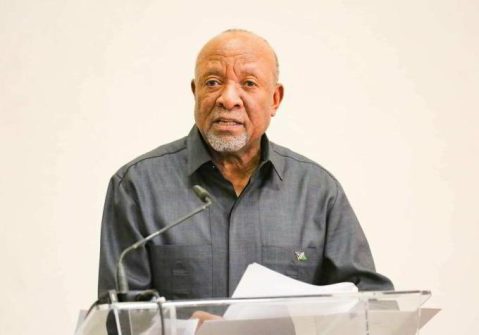

Meanwhile, Tenzin Gyatso has already hinted several times that his reincarnation could emerge outside Tibet to avoid Beijing’s interference in the selection process. The successor could be from one of the territories where Tibetan Buddhism is practised, in particular Nepal, Bhutan or, indeed, Mongolia. The Chinese Communist Party has so far remained silent, but has no intention of giving up what it considers its right to nominate. A few months ago, the current leader of the Tibetan government in exile, Penpa Tsering, declared during a trip to Australia that, if Beijing maintains its intention to appoint its own Dalai Lama, there will soon be two.

The first issue that Beijing should address is the management of the post-double appointment on its territory. Particularly in the Tibet autonomous region, where some might be tempted to follow the instructions coming from the authorities in exile rather than those of the Communist Party. All this would risk reopening a dossier that Chinese officials are convinced they had archived after the repression of the protests in 2008, in the months preceding the Beijing Olympic Games.

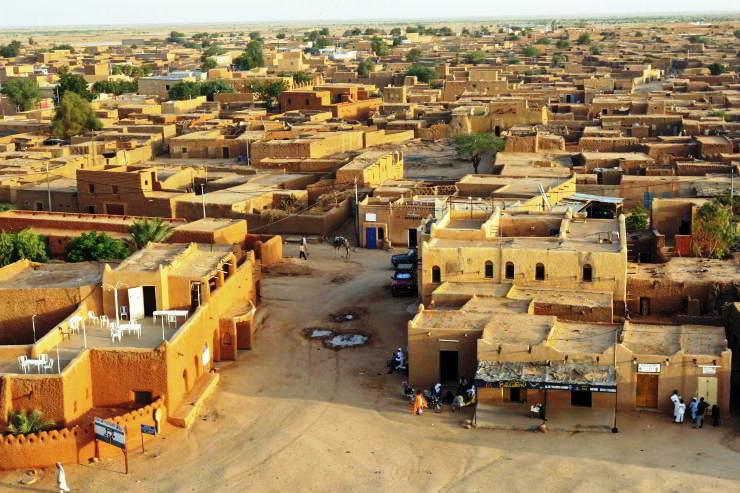

Perhaps this is also why the two-track policy with which Tibet’s integration has been strengthened has been intensified in recent years. The first track is the economic one. In the space of just over 70 years, around 255 billion dollars have been invested in the region in infrastructure and other projects. In the 14th five-year plan (2021-2025), another 30 billion have been allocated, especially for projects related to the transport sector.

Lhasa town and surrounding mountains in Tibet. “Project of the century”, a new railway which, when completed will connect Lhasa (in Tibet) to the capital of Sichuan, Chengdu. Shutterstock/Arnaud Martinez

Work is underway on the so-called “project of the century”, a new railway which, when completed (expected in 2030), will connect Lhasa (in Tibet) to the capital of Sichuan, Chengdu, in just 12 hours: a third of the time currently needed to travel by road. The second track is the cultural one. Alongside investments, Beijing has promoted the settlement of ethnic Han Chinese in the region and domestic tourism towards Tibet, which between 2016 and 2020 brought over 160 million tourists to the region from other Chinese provinces. Sensational numbers if you consider that in 2005 Tibet received less than two million visits a year.

In addition to Tibet, also Xinjiang (a Muslim majority province) and, to a lesser extent, Inner Mongolia. Communication is also important in this strategy. It is no coincidence that from 2022 onwards the Chinese authorities and media will increasingly use Tibet’s Mandarin name, Xizang (often translated into “treasure of the West” due to its position on the map of the People’s Republic). Above all, it is no coincidence that they do so in press releases or content in English. The message to the outside is clear: “The Tibetan issue is purely Chinese”, for which Beijing therefore expects compliance with its famous diplomatic principle of “non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries”.

India is not just an onlooker

In reality, India, which hosts the Tibetan authorities in exile on its territory, has also been involved in the issue for some time. In New Delhi, ample space is given to the Dalai Lama’s manoeuvres, especially when he goes near the endlessly disputed border between India and China. In the summer of 2022, Dalai Lama “deployed”, with the assistance of the Indian government, to Ladakh, near the disputed territories, where he gave a speech critical of the Chinese government. The territorial dispute is precisely grafted onto that of Tenzin Gyatso’s succession. The Buddhist leader in fact lives in exile not far from a border that remains hot.

In June 2020, there were several casualties caused by clashes between the militaries of the two sides. Several other incidents were also recorded in subsequent years. A situation that remains volatile after several rounds of talks produced no significant agreements. Beijing and New Delhi continue to reiterate their respective claims of sovereignty over a highly strategic area also for its water resources, another element that will become increasingly crucial in the future.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. India hosts the Tibetan authorities in exile on its territory. Photo. Pres. Office.

In September 2023, on the eve of the G20 summit in New Delhi which Chinese President Xi Jinping did not attend, the Beijing government presented a new map of the borders of the People’s Republic with the various territories disputed with India. Several places in what China calls “Southern Tibet” and now part of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, were renamed with Mandarin names. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi saw it as an insult, coming just as he was hosting the event that he had presented as the flagship of his second mandate.

In the background, but not too distant, is the United States which, with the war in Ukraine, is trying to strengthen military ties with India, also providing satellite and defensive technology potentially useful in a scenario of confrontation on the border with China. Washington will most likely be in the front row in supporting the Dalai Lama whom Beijing will deem “illegal”, forcefully returning Tibet (or Xizang) to the top of the agenda of the most delicate dossiers of relations between the two powers. (Open Photo: Dalai Lama. Ven Tenzin Jamphel/OHHDL)

Lorenzo Lamperti/MC