Mexico. An Aztec Legend. The Princess of the Night.

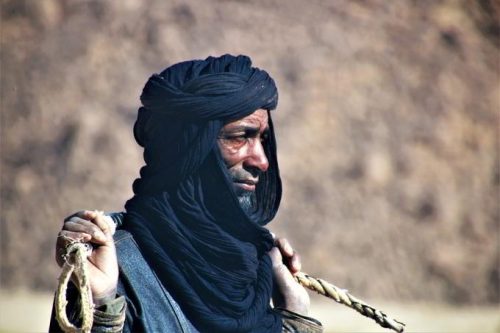

As the sun sets over the stony plateau of Mexico, a beautiful white flower opens its corolla among the blade-like thorns of the Cereus Nycticalis: it is called the Princess of the Night.

When the king of Michoacan sent out the town criers to the villages and districts, all the maidens came out from their terraces to hear their voices. The town criers shouted: “By order of the king, all maidens of all ranks and classes are invited to take part in the flower contest. The one, rich or poor, beautiful or ugly, who brings the strangest flower to the palace, a hitherto unknown corolla, will become the bride of Prince Tutul!

And on the terraces, loud chattering had begun; how many hopes had been lost! Who could ever find a new flower, never seen before, on those sun-baked hills, with their cracked stones, where only the cactuses stretch their twisted arms towards the blue sky?The maidens shook their heads in melancholy and the wise old women murmured: “Prince Tutul, with his passion for flowers, will be left without a bride…”.

But one girl had not lost hope: Red Star paced her room, trying to think of a way to win the race and become the Princess of Michoacan! “Go away, Moonbeam! – she cried to the faithful maid who had approached her – I have no desire to listen to your lamentations today! I have much to do and think about so leave me alone!”

“Red Star, my lady, I know what you are thinking and I want to help you…,” said the faithful maid. “What do you want to do? You are a slave, and if I, a noble and cultured woman, cannot find anything, what hope have you?”, replied Red Star

Moonbeam insisted: “If you let me go, my lady, for your sake I will search the whole plateau and find the strange flower that will allow you to marry Tutul. I am sure I will succeed.”

Red Star looked at her and said: Will you? You mean you can do as well as I can? All right, Moonbeam, go ahead… but remember one thing: if you come back empty-handed, you will be severely punished! You feel capable of so much. You have to risk something. Go now, but don’t forget the punishment!”

Taggio di Luna stumbled across the plateau, walking for days under the relentless, scorching sun: her feet, torn by the stones, bled with every step; soaked with sweat, her hair had stuck to her shoulders… how tired she was! And she was searching in vain.

********

Moonbeam stopped at every bush and searched anxiously among the thorns: nothing. Not a single flower. And if there was one, shy and half-hidden, it was a common corolla that bloomed even in Prince

Tutul’s gardens.

But Moonbeam resumed the path and the patient search, growing weary. She did not want to return not for fear of punishment, but because she loved her mistress and would even give her life to help her, even though she knew Red Star would never be grateful for the sacrifice.

One evening, tired beyond endurance, Moonbeam sat down by a thorny, barren, tall stalk to rest a little. The girl thought sadly that twenty days had passed since the cry of banishment and nothing had been found…

“I have barely a week left! – she muttered to herself, – I’ll never find a flower to make Red Star and Tutul happy … My mistress was right, what hope could there be for a poor slave girl like me? I was too presumptuous …” A flutter of wings interrupted her thoughts; struggling in vain to resume its weary flight, a hummingbird fell at the girl’s feet.

“Poor thing… – Moonbeam took the exhausted hummingbird in her hands – what are you doing here, where there is only sunshine and burning stones? … oh, you cannot answer, hummingbird … Open your beak. Are you thirsty? I too am thirsty and I have no water …”

The hummingbird opened its beak and waved its little head, breathing with difficulty. The girls said: “How I pity you, … But… Wait! I want to try to break this plant. If a single drop of water falls from its stem, it will be for you. I can wait!”

Moonbeam placed the hummingbird in the shade under a rock ledge and, climbing over a pile of stones, managed to grasp the stem of the cactus, which jutted sharply like a sword from the thorny bush. Leaning against it, the maiden leaped to the foot of the plant, passing through the thorns that pierced her bare feet and legs, tearing her skin; she bent over the top of the bush and, pressing down with all her weight, managed to break off its top.

The sharp thorns also pierced her chest and throat… But a drop of water formed on the break in the fleshy bush. At the end of her strength. Moonbeam broke the thorny bush again and knelt down beside the hummingbird, and the drop that fell from the broken cactus wet the hummingbird’s throat. Reanimated, the hummingbird opened its shining eyes and with a flap of its wings rose into the air.

“Fly… fly! I’m glad I could give you back some strength!” Moonbeam smiled at the multi-coloured wings of the bird as she knelt on the burning rocks. The bird circled her head three times, as if to thank her, then headed for the distant line of the horizon; hardly able to raise her weak hands, Moonbeam waved wearily, then fell into a deep sleep in the shadow of the rock, where the hummingbird of a hundred colours had rested a short while before.

When, at dawn, the little girl opened her eyes again, she felt a strange force creeping through her veins. “I am no longer tired! And I am no longer thirsty.” – she exclaimed in amazement, rising to her feet, – … “Oh, what a wonderful flower!”

There where the cactus was broken, a large corolla, white and odourless, shone in the pale light of dawn; it was the most beautiful flower Moonbeam had ever seen. Red Star, his lady, would marry Prince Tutul.

Happy, Moonbeam plucked the white flower, closed it in a basket, and ran down the stony slope towards Michoacan. She ran, happy with her discovery and new strength, without thinking how the beautiful corolla had come into being in the night, and without even thinking that she and only she could win the race and become a princess …

********

“Here is the flower, my lady!” – said Moonbeam, kneeling at Red Star’s feet. I have kept my promise in time: tomorrow you can be declared the winner of the race.”

Without a word of thanks, and wrinkling her nose at the sight of the maid’s bloodied and dusty limbs, the magnificent Red Star took the basket and gazed for a long moment into Moonbeam’s smiling face.

Red Star said: “I hope no one knows…” Quickly the girl replied: “Oh, no, my lady! I have not spoken to anyone!” “But you might as well speak, Moonbeam… you never know! And then you would be the Princess of Michoacan!… Xilo! Huitzli! Come here!”

Two strong slaves entered through the small door leading to the terrace. “Take Moonbeam and throw her in the dungeon! She shall never come out, and no one shall speak to her!”, said Red Star. Deaf to the poor girl’s cries and moans, the two slaves locked Moonbeam in the dark dungeon.

********

After placing the magnificent white flower in a precious vase, Tutul gave orders for his wedding to be celebrated with Red Star the next day. The prince was not happy with his fiancée but what could he do? The proclamation had been clear, and no other maiden with such a strange and beautiful corolla had appeared at the contest.

Sighing, Tutul went to his room to choose the jewels to send to Red Star as a wedding present. On the chest, under the compartment that was open like a window in the wall, the prince found a hummingbird of a hundred colours. When the bird saw him, it flew to his shoulder and caressed his cheek with its beak.

“What do you want, hummingbird? And how did you get here?” said Prince Tutul. The hummingbird answered: “ It is “Five Flowers”, Mocuilxochtl, protector of flowers and dance, who sends me to you, Prince Tutul. It was Five Flowers, who produced the white corolla that now rests in your polychrome vase, a corolla that recalls the compassion of Moonbeam, your fiancée’s slave.

It is she who saved my life, it is she who walked day and night in search of a flower that would please you. …. It is she who must be your bride!”

The prince asked: “Where is this girl, little hummingbird?” “In the dungeon of Red Star’s Palace”, the hummingbird said and flew away.

********

And so it was that the faithful slave, the brave, good and humble Moonbeam, became the bride of the Prince of Michoacan. In memory of her, the beautiful large white corollas on the thorny arms of the ‘cereus’, which open only in the middle of the night and radiate an almost lunar light, are called “Princesses of the night”. (Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0/Ks.mini)

Aztec Legend