West Africa. Winds of resource nationalism blow across the Sahel.

Following the expulsion of French troops from Mali, Burkina-Faso and Niger, the leaders of these countries are extending their pro-sovereignty policies to the economic sphere. Together with Senegal, they have embarked on a new policy of resource nationalism.

One of the key figures behind these changes is Kemi Seba, whose real name is Stellio Gilles Robert Capo Chichi, a 43-year-old French-Beninois binational who has been advising Niger’s president, General Abdourahmane Tiani, since August 2024, a year after the July 2023 military coup that ousted the pro-French president Mohamed Bazoum. Kemi Seba, who founded the NGO “Urgences panafricanistes”, claims to be a successor to Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement and to have been trained by Louis Farakhan’s Nation of Islam.

Kemi Seba. CC BY-SA 4.0/Boubs Sidibe

He sees himself as the spiritual heir of the late presidents of Ghana, Kwame Krumah, and Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara, although for a time he adopted black supremacist rhetoric. For several years he has been campaigning against the “degenerate neo-liberal global elite” and the CFA franc, which he considers to be a neo-colonial currency. In an interview published last October by the Turkish news agency Anadolu, Kemi Seba, who describes Niger as a “laboratory of the Pan-Africanist revolution”, announced his ambition to liberate the Sahel from the transnational corporations that exploit the region.In addition to the withdrawal of French troops from Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger between 2022 and 2024, the three countries of the Alliance of Sahel States, founded in July 2024, have begun to rename streets and monuments that recall the French colonial past. On 18 December 2024, 25 squares, streets and monuments in Bamako changed their names. The streets of Faidherbe, Brière de l’Isle and Archinard now bear the names of local heroes such as Mamadou Lamine Drame, Banzoumana Sissoko and El Hadj Cheick Oumar Tall. Similar decisions were taken in Burkina Faso last April and in Niamey last October. Last December, Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye also called for the renaming of several avenues in Dakar to honour the country’s heroes.

The ruling military leaders, from the left: Capt Ibrahim Traoré (Burkina Faso) Colonel Assimi Goita (Mali) General Abdourahmane Tchiani (Niger). Photo Archive

Since 2023, the members of the Alliance of Sahel States have been pursuing a policy of resource nationalism. The first shot in this nationalist crusade came from Burkina Faso, where in February 2023 the junta seized 200 kilograms of gold mined by a subsidiary of the Canadian group Endeavour Mining on the grounds of “public necessity”.

Then, in 2024, the Burkinabé junta nationalised the Boungou and Wahgnion gold mines, which were owned by Canadian miner Endeavour Mining. The plan is also to increase domestic processing of local ores, as evidenced by the government’s approval in November 2023 of the construction of Burkina Faso’s first gold refinery.

“We are going to get our mining licenses back,” Burkina Faso’s President Ibrahim Traoré stated earlier this year “and we are going to mine it ourselves”, he said. This nationalisation process meant a renegotiation of contracts with foreign firms and the assertion of more control

over the mining operations.

On 2 January 2025, a judge in Mali ordered the seizure of three tonnes of gold from the Canadian mining company Barrick Gold, which owes the government a total of $5.5 billion. The decision follows a dispute with the Malian authorities over a contract based on new mining regulations, during which Mali detained senior executives and issued an arrest warrant for Barrick’s CEO, Mark Bristow.

Loulo-Gounkoto Gold Mine Complex in Mali. Photo: Endeavour Mining

The government then seized the stocks from Barrick’s Loulo and Gounkoto mines in western Mali and transported them by helicopter to the state-owned Banque Malienne de Solidarité in the capital, Bamako.

As a result, Barrick announced on 13 January 2025 that it would have to suspend mining operations in the country and filed a request for arbitration against Mali with the Washington-based International Centre for Settlement of Investment. Two weeks later, the Bamako government and Barrick began negotiations to resolve the dispute over the Canadian mining company’s alleged non-payment of taxes, the seizure of its gold stocks and Barrick’s agreement to the new mining code, which gives the state a greater share of mining revenues and eliminates tax exemptions for mining companies.

In November 2024, the Malian military also arrested the CEO and two employees of Australian company Resolute Mining, before releasing them after the company signed a $160 million deal with the government. Other mining companies, such as Canada’s Allied Gold, B2Gold and Robex, did not face such problems because they had previously agreed to review the terms of their contracts and paid to settle tax and customs disputes.So far, Mali has raised more than $1 billion by negotiating new contracts or renegotiating old ones, according to Economy Minister Alousseni Sanou. Reforms in the mining sector are expected to bring in another billion dollars a year and increase the national budget by 20 per cent. The leader of Mali’s junta, General Assimi Goita, also said in January that these new revenues would make it possible “to pay off part of the internal and external debt and to pay for military equipment”.

Uranium mine in Niger. The Niamey government has announced that Niger will seek to attract Russian investment in the uranium sector. File swm

Meanwhile, in the wake of the July 2023 coup, Niger’s military junta withdrew the licence for the Imamouren uranium mine held by French nuclear giant Orano on 19 June 2024. This is a serious blow to Orano, which is 90 per cent owned by the French state, as Imamouren is one of the world’s largest deposits, with an estimated total of 200,000 tonnes.

Then, in October 2024, Orano announced that its subsidiary Somaïr, 63.4% owned by the French company and 36.6% by the State of Niger, would cease production because, according to management, it could no longer operate in the country. Shortly afterwards, on 8 November, the mining minister, Ousmane Abarchi, announced that Niger was seeking to attract Russian investment in the uranium sector. The Niamey authorities also took operational control of Somaïr at the end of 2024, while Orano retaliated on 20 December by announcing its intention to take Niger to international arbitration.

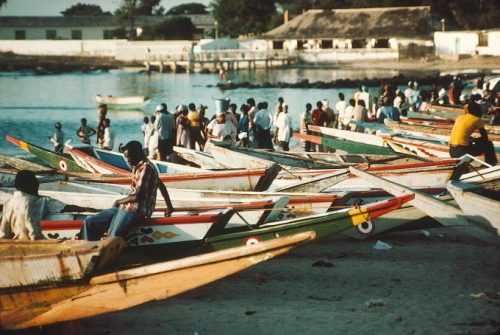

The new government in Dakar states: “We cannot continue to sign agreements that end up impoverishing the 50,000 local fishermen whose pirogues no longer have access to the resource that is being depleted by foreign fleets”.

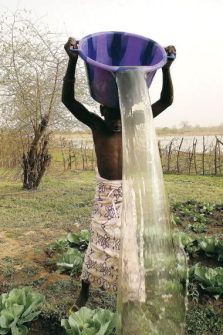

The wave of resource nationalism has also reached Senegal. On 17 November last year, the government in Dakar announced the end of the fishing agreement with the European Union, in line with new policies following the election of a nationalist president in March 2024 who promised a fairer distribution of natural resource revenues for the benefit of the Senegalese people. “We cannot continue to sign agreements that end up impoverishing the 50,000 local fishermen whose pirogues no longer have access to the resource that is being depleted by foreign fleets of factory ships, including European ones,” say the new authorities in Dakar.

Some observers warn that the Sahelian states’ new rhetoric, based on sovereignty and rejection of Western partners, risks scaring off foreign investors. But supporters of the juntas counter that new partners looking to expand their influence in the region, including China, Russia and Turkey, are ready to fill the gap. Whether the interests of the local population will be better served remains to be seen. (Open Photo: 123rf)

François Misser