The Catholic Church in Kazakhstan. Testifying through friendship and dialogue.

Kazakhstan is the country of Central Asia with the largest number of Catholics. Small communities scattered throughout a vast territory. The commitment of the Church to human development and social promotion.

Kazakhstan is located in Central Asia. It is the ninth-largest country in the world, with an area of 2,724,900 square kilometres. Its territory is characterized by the plains of Western Siberia and the oases and deserts of Central Asia. Before independence, during the Soviet Union period, the Kazakh population was less than 50%, the other half was composed of Russians, Ukrainians, Polish people and other immigrants of other nationalities. After the immigrants left, the situation changed and the Kazakhs now make up 63% of the population with 17.5 million inhabitants. The capital of the country is Nur-Sultan (formerly Astana).

The semi-arid steppes characterized by freezing temperatures in winter, turn into endless meadows ideal for pasture in spring, an essential resource for the Kazakh people who are also skilled horse riders since horses have always been essential for their nomadic lifestyle. The Kazakhs are said to have been the inventors of stirrups. They are also very skilled at shooting arrows while riding a galloping horse. Still today they perform their particular skills during parties and events. Their handicrafts made of felt, or wool are lavishly decorated. Headdresses, dresses, bags and saddle-cloths are beautifully embroidered. They use traditional designs and carvings to make and decorate the wooden cups, large bowls and ladles used to serve kumis (fermented mare’s milk). The foundation of Kazakh culture is hospitality, which always starts with a cup of tea. The host offers tea to any person who comes to their yurt. The yurt is a dome-shaped felt tent, a sort of elaboration of the Mongolian tent. It is a movable, comfortable and practical home, ideally suited to local conditions. The main material in yurt construction has always been willow wood. Once the framework is constructed, a felt cover provides protection from wind, rain, and snow in winter, and the scorching sun and dust of summer.

The Kazakh culture has its roots in the nomadic nature of the people and in Islam, which is the religion professed by the majority (70%) of the inhabitants of Kazakhstan. The Kazakhs embraced Islam during the sixteenth century and still consider themselves Muslim today. Changes in Kazakh society (mainly from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle) and an attempt by the Soviets to suppress religious freedoms, have led the people to adopt Islam more closely. However, their Islamic practices have been combined with traditional folk traditions such as shamanic practices, ancestor worship, etc. At the basis of the Kazakh social organization there is the extended patrilocal family. One of the most ancient forms of marriage among the Kazakhs was abduction, in which, under certain circumstances, the young man abducted his future wife either with her agreement or without it.

Marriage through abduction is still rather widespread, especially in rural areas. This is today only an imitation of abduction, however, since the girl, as a rule, willingly goes to the groom’s home ‘surreptitiously’. In such instances, the wedding is arranged immediately. The groom’s parents ask forgiveness from the bride’s parents, who give it. After the wedding the bride’s dowry is brought.

As a rule, patrilocal marriage predominates among the Kazakhs. However, levirate marriages are also common in Kazakhstan. In accord with the custom of levirate, after the death of her husband, the widow, together with the children and all the property of the deceased, is inherited by his brother (i.e., she becomes his wife). In accord with custom, Kazakh men can have several wives.

As for poetry, the Kazakh poetic styles reflect the Kazakh lifestyle, views, and ideals. The main styles of verbal-poetical art are: epic poems, social-domestic poetry, lyric-dramatic epos and lyric poetry, historical songs, shepherd’s lays, magical chants, wedding and funeral songs, fairy-tales and legends.

The Catholic Church

Kazakhstan is now the Central Asian country with the largest number of Catholics. It can be said that the history of the Catholic Church in Kazakhstan resumed in the 20th century when Stalin ordered the deportation to Central Asia of whole peoples of the Catholic tradition. From 1930 onwards, many priests were deported and sent to concentration camps in Kazakhstan. Having been released, they settled among the people and began clandestine ministry.

In September 2001, Pope John Paul II visited the small Catholic community which had gained new vigour after independence. In 2003 the Episcopal Conference of Kazakhstan was created. This is composed of the dioceses of Nur-Sultan, Karaganda (led by Msgr. Adelio Dell’Oro) and of the Holy Trinity of Almaty (led by Msgr. Jose Luis Mumbiela Sierra); in addition, there are the apostolic administrations of Atyrau (governed by Fr Dariusz Buras) and that of the Byzantine rite Catholics in Kazakhstan and Central Asia (led by Fr Vasyl Hovera).The Catholics are around 1.14% of the population (about 112 thousand). There are currently 70 parishes in the country. Religious of 20 different nationalities reside in the area, for a total of 120 priests and 130 nuns. At present, there are 80 Roman Catholic religious associations in Kazakhstan. All of them have passed the procedure of re-registration and are among the 18 denominations officially registered in Kazakhstan.

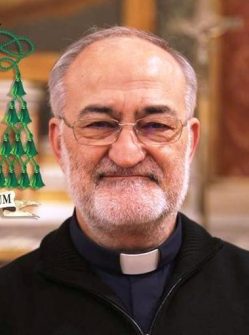

Msgr. José Luis Mumbiela Sierra is also president of the Episcopal Conference of Kazakhstan. “The Catholic Church is going through a process of transformation. Initially most of the faithful were descendants of Polish people, Germans, Ukrainians and Baltic people, who had been deported during Stalin’s rule in the past century. Many of them have emigrated to other countries, but at the same time, people of other nationalities who ‘traditionally’ were not Catholics and not even Christians are now joining the Catholic faith. This constitutes a challenge for evangelization and inculturation. The migration phenomenon affects us closely, but we do not consider it a problem”, says the bishop.

“There is an atmosphere of dialogue and friendship in Kazakhstan. The government itself, ever since independence in 1991, has endeavoured to promote a society based on good relations between the different religious faiths. Peace and harmony are everyone’s goal and joint meetings are organized for this purpose. In this context, rather than institutional relations, personal relationships are important, relationships of closeness and friendship between believers of different religions or even non-believers”, says the bishop.

Msgr. Mumbiela recalls Pope John Paul II’s visit in 2001. “It was an unforgettable moment of grace and blessing. I believe that for Catholics who lived through the difficult years of the Soviet era, it was like seeing the light at last after going out of the catacombs. There were also many non-Christians who recognized that a ‘holy man’ had come among them. To us he was, and still is, a strong call to holiness. Missionaries are responsible for the image of the faith they profess. The Gospel must be made credible, acceptable and desirable for its beauty that missionaries should transmit through the testimony of their life “.

The Catholic Church, which is a minority community in Kazakhstan, has strengthened its presence in social works. Caritas in the country is very committed to human development and promotion. Two projects have recently been launched. One project is designed to provide training for staff working with adults and children with disabilities. Caritas director Don Guido Trezzani says, “We are creating two greenhouses, one in Talgar and the other in Almaty, which will also give the opportunity to teach disabled children a possible occupation by learning how to cultivate agricultural products”.

The other project involves women. It is a micro credit project, “We have purchased sewing machines to produce eco-bags which, as Caritas, we are already selling and distributing. With the help of potential partners or sponsors, we plan to buy more sewing machines to make bags and involve other women. Once the participants have returned the credit, they will decide whether to continue working with us or to start their own business”.

Archbishop Dariusz Buras Apostolic Administrator of Atyrau, says, “Over the last twenty years we have experienced very important events: the opening of churches and pastoral centres in cities such as Atyrau, Kulsary, Uralsk, Aktobe and Khromtau. Other occasions of joy were the two priestly ordinations of 2017 and 2019: Father Ruslan Mursaitov was the first local priest of the Apostolic Administration of Atyrau. Last year God gave us a second priest, the Philippine Father Patrick Napal”.

The Apostolic Administration of Atyrau is currently composed of six parishes located in four regions of western Kazakhstan and it is run by 15 priests and seven nuns: “The number of parishioners is constantly increasing. There are about 500 local Catholics in western Kazakhstan, to whom are added the many foreigners who come to work in this area and participate in the life of the Church”. (C.C.)