After decades of distrust and hostility, the Somali brothers from Mogadishu, from the break-away state of Somaliland and from the federal states of Somalia are talking to each other. Regional and international partners are trying to help. Meanwhile, Somalia’s parliament removed Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire from his post in a vote of no confidence for failing to pave the way towards fully democratic elections.

For the first time since the former British colony of Somaliland broke away from Somalia after the overthrow of the dictator Siad Barre in 1991, the leaders of Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, nicknamed ‘Farmajo’ (a deformation of his father’s own nickname, “Formaggio” or cheese in Italian), and his Somaliland’s President Muse Bihi Abdi, held official talks in Djibouti on the last 14 June.

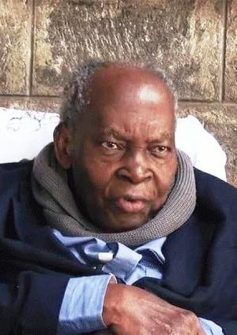

The president of Somalia Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo.

The ambition of the host, President Ismail Omar Guelleh and of the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abyi Ahmed who attended also the meeting and who had brokered an informal face-to-face discussion between the two, in February was to have Farmajo and Bihi seated at a same table. In itself, the presence of both leaders in Djibouti was an achievement. Indeed, in 2019, the International Crisis Group think tank reminded in a report that the relationship had become extremely tense. During several rounds of talks between 2012 and 2015, both sides made some progress on practical issues of cooperation such as airspace management, but failed to close the gap on the Somaliland’s status and eventually the talks collapsed. There were clashes between Somaliland forces and those of the neighbouring semi-autonomous Puntland region of Somalia, in 2018.

The president of Somaliland H.E Musa Bihi Abdi

Conflicting interests from regional partners contributed to the deterioration of the situation. The Mogadishu-based Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) felt very upset after the Dubai-based DP World Company which operates the port of Berbera, in Somaliland, offered Ethiopia a stake in the harbour in 2018. The Mogadishu government claimed that such agreement was “a violation of its sovereignty”. At the same time, the Emirati company, which also manage the port of Bosaso in Puntland, was unlikely to welcome negotiations in which Somaliland could be pressed to yield decision-making power to Mogadishu on issues that might affect its interests.

Somaliland’s President Bihi called Somalia’s opposition to the Berbera deal a “declaration of war”.

The Horn of Africa has become a field for the confrontation of interests between the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia on one hand, and Qatar and Turkey on the other, like it happens in Libya. During the Covid 19 crisis, the Ukrainian air company Zet Avia which delivered weapons to the Libyan general Khalifa Haftar on behalf of the UAE, transported cargos of medicines to Somaliland and Puntland. Meanwhile, Qatar and Turkey which support the Tripoli government in Libya are backing the Mogadishu authorities.

Some positive developments occurred recently, however. The Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wished to get involved in the detente process. Turkey’s ambassador in Mogadishu, Olgan Bekar who had carried out mediation efforts between Somaliland and Somalia also attended the Djibouti talks. This added to similar attempts from Ethiopia, Djibouti, Sweden and Switzerland. The foreign partners insisted that the defeat of Al Shabaab’s insurgency required Mogadishu and Hargeisa to share intelligence and pool resources.

All this contributed to ease the tensions and to create a momentum towards renewing negotiations. Other partners tried to consolidate the process by expressing their support. The list includes the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, the European Union, the United Kingdom, the African Union Mission in Somalia, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Uganda, the United States and the UN. No agenda was made public. Insiders say that the plan was to focus primarily on designing modalities for future dialogues rather than on the thorny question of statehood. Before the Djibouti meeting, President Bihi had indeed still declared that the Mogadishu authorities were the biggest challenge for Somaliland’s fight for recognition as an independent state.

One of the main outcomes of the meeting was the setting up of a joint ministerial committee tasked with spearheading dialogue between both sides. Somalia’s Interior minister Abdi Mohamed Subriye and Somaliland’s foreign affairs boss Yasin Hagi Mohamud were appointed as co-chairmen of this committee.

One week after the beginning of the talks, Djibouti declared that a “tremendous progress” had been made and that the delegates had discussed in a “warm and brotherly atmosphere” in presence of Djibouti’s Foreign Affairs minister Mahmoud Ali Youssouf and of the facilitation from the US and the EU.

The committee met from June 15-17. As part of the goodwill gesture, both parties agreed to refrain from acts that would otherwise impede negotiations and discussed confidence-building measures.

To narrow down the issues, both parties formed several subcommittees on humanitarian aid, investment, management of Somalia’s airspace and security matters. Both sides also agreed that the Joint Ministerial Committee would resume talks to review the progress made by the subcommittees in early August.

Yet, while the thorny issue of Somaliland’s international recognition was not discussed, the Hargeisa authorities still maintain that the issue should form part of the agenda, ultimately.

Time will tell whether progress can be recorded on this sensitive issue. Yet, the first reactions about the Djibouti meeting were positive: Somalia’s Interior Minister, Abdi Mohamed Sabrie, said that his government was committed to have a “genuine dialogue” with Somaliland. According to the Foreign Minister of Somaliland, Yasin Faraton, the talks were “a step in the right direction”.

The former US ambassador in Ethiopia, David Shinn, now professor of international affairs at The George Washington University, in an interview with the Horn Tribune suggested that rather than total independence for Somaliland, which would not be agreed in the international arena, a possible compromise solution could be a confederated status for Somaliland whereby it would maintain considerable autonomy. In his view, the question of the recognition of Somaliland should be determined by the African Union. So far, the AU has shown reluctant since it seeks to avoid to open a pandora box. But the Somaliland case is a challenge for the organization since according to the AU’s principle of intangibility of borders inherited from colonization, Somaliland which was colonised by the British and Somalia which was an Italian colony, declared independence separately in 1960 before agreeing to form a single Somali Republic, were different states. At the same time, AU member states do not want secessionists in South-Western Cameroon, Cabinda or Katanga to use the precedent case of an internationally recognised independent Somaliland, to promote their cause.

The road of reconciliation is difficult. Both sides face the opposition of hardliners. In Mogadishu, President Farmajo’s speech at the Parliament was interrupted by loud whistling, boos and hisses when he declared that “President Bihi of Somaliland had accepted the talks But under Farmajo’s rule, the Federal Government of Somalia seems committed to improve its relations with all the other entities of the Somali community. On the 14 June, the FGS officially recognised the leader of the semi-autonomous Jubaland state, Ahmed Madobe after months of rising tensions and armed violence, following the re-election as president of this former warlord in August 2019 who had been boycotted by the federal government who had backed his rival. Such recognition should help to ease tensions with Kenya which backed Madobe and had escalated in March, when heavy fighting broke out near the Kenyan border between Somali troops and Jubbaland forces

The Federal Government which had faced criticism for engaging in disputes with federal states instead of focusing on the fight against Al-Shabaab, also invited heads of the various states to Mogadishu to discuss national elections. President Farmajo held virtual talks with the leaders of Puntland, South West, Galmudug and Hirshabelle.and invited all of them and Madobe as well to Mogadishu to discuss elections and also security and economic issues.The move was appreciated by Senator Ilyas Ali Hassan, the foreign secretary of the Himilo-Qaran opposition party, which is led by former president Sheikh Sharif Ahmed. “The meeting is a good gesture”, he said.

Now, concerning the forthcoming elections, a number of issues remain to be solved. One contentious proposal is whether Somalia should continue with the clan-based system in elections. Puntland state, which declared autonomy in 1991 and Jubbaland are insisting that clans should not be used in the upcoming elections.

Another bone of contention is the date of the election. In principle, a new parliament has to be installed by end November 2020 and a presidential election is scheduled at the end of June 2021. President Farmajo has pledged to hold elections on time. But the chairperson of the National Independent Electoral Commission (NIEC), Halima Ismail Ibrahim, told the Lower House of the parliament that political differences, insecurity, flooding and COVID-19 have hampered the schedule and that the election could not take place as foreseen, reported the Voice of America on the last 28 June

According to Ibrahim, the necessary biometric registration imposed by the electoral law cannot be completed in time. She says that the purchase of registration equipment, the security of registration sites, the registration of voters and candidates and the establishment of the voters’ registry need more time and budget. In her view, at least 13 months are necessary to meet these conditions.

The main opposition coalition, the Forum for National Parties (FNP), which brings together six political parties, is outraged and has called on the electoral commission to resign for failing to hold the election on schedule. It has accused the NIEC of collaborating with the current government on term extension.

Nevertheless, some useful steps are taking place to mend the gap between the federal government and the regional states whose relations are extremely difficult. Progress was recorded with the signature of a badly needed cooperation security deal between Puntland and the neighbouring state of Galmadug as both entities are struggling to cope with an escalation of Al-Shabaab attacks. In April, Al-Shabaab militants launched attacks on the rather peaceful Puntland from Galmadug, during which they shot dead Nugal Governor Abdisalam Hassan Hersi in Garowe, the regional administrative capital of Puntland.Meanwhile, on July 25th Somalia’s parliament removed Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire from his post in a vote of no confidence for failing to pave the way towards fully democratic elections. A whopping 170 of parliament’s 178 MPs backed the no confidence motion, and Khaire’s ouster was immediately endorsed by President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo, who had appointed him as prime minister in February 2017.

François Misser