Music. The Sarkodie Generation.

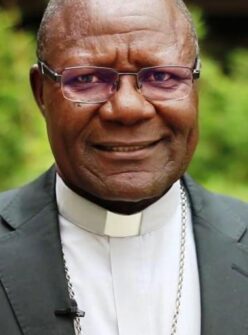

The head of a musical movement that is both cultural and profitable, Michael Kwesi Owusu Addo, known professionally as Sarkodie, achieved this position due to the stylistic ductility and the quality of his texts in the Twi language.

With the international emergence of modern African music, in the eighties, a number of stars of that continent attracted attention: Fela Kuti, King Sunny Ade, Youssou Ndour, Mory Kanté and Franco, to name but a few. However, while those interested in ‘world music’ had just begun to be familiar with this universe hitherto unknown to the majority, starting with the late eighties, the African music scene began a process of profound transformation. Rap began to attract young Africans and, in the following decades, it took the lead among the new generations of many Sub-Saharan countries, at least in the urban centres while new and original forms of dance music based on electronics also became popular.

Among the former typical names, some are now deceased but others, like Youssou Ndour, are still famous. Any close observer of the African musical panorama over recent decades will have noticed that they have not really been replaced but that the number of great figures also known internationally has been reduced. Anyone looking at African music today through the lens of world music, which with its special labels continues to diffuse the image of the African music most loved in the West, romantic and reassuring, would not realise that many great stars were born once the new trends became established and matured. But they are more like American rappers or popular DJs than the old stars of African music to whom we had grown accustomed.

Rap and Clothing

Sarkodie is the symbol of this new generation. Born in 1988, his original name is Michael Kwesi Owusu Addo. He began to do rap as a boy. He obtained a diploma in graphic design and soon became known in hip-hop circles winning several rap contests. This brought him into contact with Hammer of the Last Two, an important Ghanaian producer who launched him with immediate success.

Released in 2009, ‘Makye’, his debut album, earned him as many as five prizes at the 2010 Ghana Music Awards: ‘artist’, ‘discovery’, ‘hip hop artist’, ‘best rapper’ and ‘album of the year’.

Sarkodie has continued winning Ghanaian and Nigerian awards and has issued four more albums: his latest, ‘Highest’, was released in September. In 2014, he created his own record label, ‘Sarkcess Music’.

Forbes, the USA economy and finance magazine, indicated Sarkodie as one of the ten richest musicians in the continent. Sarkodie has also associated his name with several trademarks: in 2013, he launched his own line of clothes and also a foundation to help underprivileged children. Together with other musicians (among them the Nigerian Davido, another emblematic star) in 2014 he collaborated in composing a song for a campaign to promote participation in communitarian

and social investments.

Sarkodie’s success is due to the smooth style of his rapping with an ability to improvise, his flexible style, and the quality of his texts, mostly in the Twi language, which are concerned with local and daily life situations, and have an uplifting content. The general quality is very high and there is much sophistication in the clips derived from his compositions that are shown on YouTube in an infinity of visual arrangements. To get some idea of this, it is enough to view ‘Trumpet’, released at the end of 2016, in which Sarkodie offers a spot to six emerging rappers in a clip that, by its essential nature, wonderfully holds the attention for the full nine minutes it lasts.

Sarkodie released his fifth studio album Highest on 8 September 2017. It comprises 19 songs, including 3 interludes and a bonus track. Finally, on December 20, 2019, he released his sixth studio album Black Love, where he explores themes of black love and relationships.

Sarkodie married Tracy in a private wedding ceremony held in Tema, Ghana on 17 July 2018. They have two kids: a daughter, Adalyn Owusu Addo and a son; Michael Nana Yaw Owusu Addo Jnr., who is named after the famous rapper.

Franz Coriasco