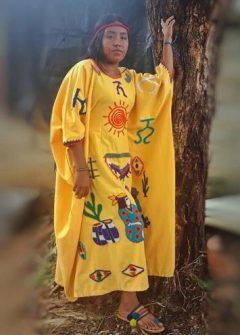

Maria Ressa. Information that gives hope.

“We want to create a federation of international journalistic organisations that collaborate in this effort, starting from the global South,” says Filipino journalist and 2022 Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa.

Sixty-one years old, a former investigative television reporter for CNN from Southeast Asia, since 2011 she has been the soul of Rappler, a Philippine information portal that has become the symbol of a free press in a country where family dynasties and their interests have

always dominated politics.

Maria Ressa repeatedly reminds us of how, in recent years, social networks have been increasingly used to spread fake news and attack opponents. This transforms the violence of social networks

into physical violence.

“It was still 2016 – she says – when we at Rappler published the results of an investigation showing the existence of 26 fake Facebook accounts capable of influencing 3 million profiles alone. They had started by attacking journalists, activists, opposition politicians. And through the mechanism of social media, this fake news spread everywhere. Two years later, MIT in Boston confirmed it with its own study: ‘Fake news travels six times faster online than other news’”.

From there to violence, it was just a short step: “Social media do not work on rationality but on emotions” – she continues -. When I started working as a television reporter, 39 years ago, they taught me that the first 10 seconds of my report would be crucial to capture people’s attention. Today some studies say that the audience we address has an attention span similar to that of a goldfish: less than 3 seconds”. And it is in this context that having all the data available to reach us can become a terrifying weapon in the hands of the powerful.”

“Every time we published an investigation on Rappler, the response was to attack me for my eczema, a physical weakness of mine – says the journalist -. They started circulating memes in which they depicted me as Scroto Face. A sexist insult, to discredit me and even more to dehumanize me, the premise that paves the way for all violence. Judicial investigations and arrest warrant only came at the end of this journey. And it happens even more often if you are a woman or if you belong to a minority: a UNESCO survey found that 73% of female journalists have experienced some form of abuse online.”

After the Nobel Peace Prize, Maria Ressa published an international bestseller, entitled “How to Resist a Dictator”, where the reference is to Rodrigo Duterte, president of Manila from 2016 to 2022, the man of the death squads in the fight against drugs. But her battle is not just

for the Philippines.

Since the speech given in Oslo, at the Nobel ceremony, she explained in no uncertain terms that the problem is not the dictators of the moment, but the masters of the algorithms, the large companies that, having access to all our data, place weapons as powerful as the Hiroshima atomic bomb in their hands.

“The book came out in November 2022, the same week ChatGpt was launched – she recalls -. It has been translated into 25 languages, and it is interesting to see how its title also changes in the different versions. In Japanese, for example, they focused much more on the power of social media, which is the issue that concerns us all. It was recently released in Georgia and it was touching for me to see the people who have been protesting in the streets for weeks against electoral fraud taking it with them to the demonstrations.”

“What happened to us is happening even more rapidly in other parts of the world” – Maria Ressa continues -. Last year we had elections in 74 countries, but what kind of elections were they? This year, we will see the effects. The information war, the geopolitical power games, are increasingly shamelessly exploiting the mechanisms of the platforms. Their goal is not to make us believe in something, but to make us doubt everything. It is the most effective way to paralyze people and move forward pursuing their own interests.”

If this is the scenario today, for Maria Ressa it is not true that nothing can be done to stop it. It is precisely the determination to move forward in the battle for truth in information. Rappler in the Philippines is now a company in which 120 people work. But she thinks much bigger: “In 14 years of lies and disinformation against us, we have understood that if you let them do it, they will destroy hope,” explains its founder.

She continues: “But we have also understood that the alternative exists: we need to get organized and build platforms where real people can go back to having real conversations with each other, without being manipulated for power and money. At Rappler, we have started to do this: last year, we launched an app that has a space for conversations and comments in chat where we guarantee that your data will not be manipulated by the algorithm and sold. What we are seeing is that investing in a tool like this improves communication: there are very few cases of people who have had to be blocked for offensive

comments towards others.”

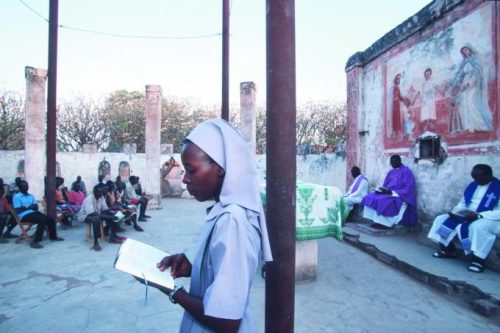

Maria Ressa points out: “We want to create a federation of international journalistic organisations that collaborate in this effort, starting from the global South. We are already working with partners in Indonesia, South Africa and Brazil; in the coming months, they should also start using our app. Collaborate. Journalists coming together to reaffirm their role in society. But this commitment alone is not enough. We no longer have control over distribution as we did in the era of traditional media. Precisely for this reason, collaborating also means recreating

networks in society.”

“One of Rappler’s strengths, for example, is fact-checking, that is, verifying the news that is circulated online. We have 16 people who do this. But it would be useless if there wasn’t another level above them, made up of 116 associations, civil society entities, religious groups that spread the results of this fact-checking in their communities, from person to person, giving life to information campaigns. And then 8 university centres that produce analyses on how lies are spread. And also six law firms to defend themselves from the attacks of those who

don’t want all this… ».

“Without facts, you can’t have the truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. And without these three things, we do not have a shared reality, much less can we solve the problems that afflict us.” Because this, in the end, is what information and democracy are for. (Photo: © Rappler)

Georgio Bernardelli/MM