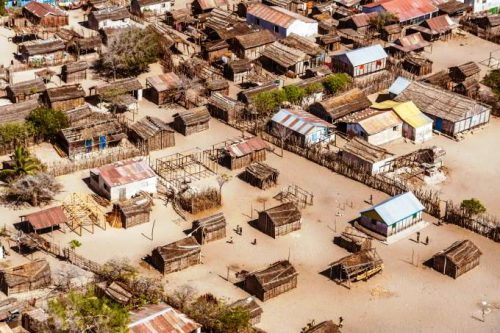

Iraq. Parliamentary Elections. A Crucial Moment.

The parliamentary elections scheduled for November 2025 represent a crucial moment for Iraq, amid profound political transformations, intra-Shiite tensions, regional pressures, and a growing disconnect between the ruling elite and the population.

As Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani seeks to consolidate his position in pursuit of a second term, the political landscape remains fragmented and unpredictable, with potential repercussions

for regional equilibrium.

Sudani, who took office in 2022 with the support of the Shia Coordination Framework (a coalition of Shia parties, some of which are pro-Iranian), is aiming for a second term. His government has distinguished itself by its emphasis on infrastructure reforms, the fight against corruption, and a certain regional diplomatic activism, culminating in the organization of the 34th Arab League Summit in Baghdad (May 17, 2025). Nonetheless, tensions with some longtime Shiite allies, primarily former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and Qais al-Khazali (leader of the Asaib Ahl al-Haq militia party), call into question his future tenure as prime minister.

Corruption allegations against some members of his coalition, including key figures such as Faleh al-Fayyadh and Nassif al-Khattabi, as well as reports of alleged vote-buying abuses by the Shiite militia of the Popular Mobilization Forces, undermine the Prime Minister’s reformist narrative. Furthermore, the decision to invite interim Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa to the Baghdad summit has fuelled internal controversy, especially among pro-Iranian factions who consider the former jihadist leader a threat to the historical memory of the victims of terrorism.

From an institutional perspective, the November 2025 elections will once again be held under a proportional system based on the Sainte-Laguë method, abandoning the SNTV (Single Non-Transferable Vote) system introduced after the Tishreen protests in 2019.

This return to proportional representation usually tends to favour consolidated or at least more structured political forces, penalizing the independent and local lists that had found space at the polls during the similar round in 2021.

In any event, the provincial elections of December 2023 highlighted the emergence of a new local political class, represented by governors and administrators who, capitalizing on growing local budgets and promises of services, managed to prevail against the old elites. A case in point is that of Nassif al-Khattabi in Karbala, a former ally of Maliki,

now close to Sudani.

The new “Reconstruction and Development” coalition launched by Sudani, which brings together the Euphrates Current, the National Pact Alliance, the National Coalition, the Creative Alliance of Karbala, the Sumerian Rally, the Generations Rally, and the Alliance of National Solutions, aims to integrate these local figures to strengthen

its territorial roots.

However, the fragmentation of the Shiite camp, with the decision of the Shiite Coordination Framework to present itself united in some provinces and divided in others (such as Baghdad), foreshadows internal (intra-Shiite) competition that could jeopardize post-electoral stability.

The other major element of uncertainty is the position of the Sadrist Movement (al-Tayyār al-Sadri). After the withdrawal of leader Muqtada al-Sadr from political life in 2022, the Movement boycotted the 2023 elections and announced it would not participate in the 2025 elections either. Nonetheless, recent calls for its supporters to update their voter registration cards have sparked speculation about a possible

indirect return of the Sadrists, through lists of “independent”

or affiliated candidates.

The Shiite Coordination Framework appears to be pursuing an ambivalent strategy: on the one hand, attempting to attract Sadrist voters with populist rhetoric and campaigns in the suburbs; on the other, spreading the narrative that Sadr could return to the polls in an attempt to reduce abstention rates, especially in Shiite strongholds

in the south.

According to preliminary data, over 9 million Iraqi voters may choose not to vote: an alarming sign for the legitimacy of the system, adding to the criticism already levelled at the Electoral Commission for its use of opaque criteria in calculating turnout.

The pre-electoral framework also includes three strategic issues: oil management, internal security, and the role of militias.

On the energy front, the conflict between Baghdad and Erbil over the management of Kurdish oil remains unresolved: the failure to implement Federal Court rulings and the blockade of exports through Turkey (with which negotiations to resume flows remain stalled) are compromising state revenues and creating friction with OPEC.

In a ruling issued in 2022, the Iraqi Federal Court declared an oil and gas law regulating the extraction industry in Iraqi Kurdistan unconstitutional and ordered the Kurdish authorities to hand over crude oil supplies to the central government.

The Iraqi Ministry of Oil believes that the Kurdish Regional Government’s (KRG) failure to comply with the law has damaged both oil exports and public revenues, forcing Baghdad to adjust production from other fields to meet OPEC quotas. Recently, the Ministry itself stated that it holds the KRG legally responsible for the continued smuggling of oil from the Kurdish region out of the country.

Recently, the Iraqi Ministry of Finance announced (May 29) that the Iraqi federal government will stop transferring funds to the KRG due to the failure to transfer oil and non-oil revenues to Baghdad, following the KRG’s May 20 signing of a multi-billion-dollar oil and gas deal

with two US companies.

Furthermore, with a view to diversifying its economic dependence on the oil and gas sectors, Baghdad is planning to develop its mining sector, signing memoranda of understanding with international companies to explore and develop resources such as phosphate, sulphur, lithium, and copper. According to government estimates, the mining sector is expected to contribute at least 10% of Iraq’s GDP during its initial development phase.

On the security front, the progressive reduction of the US military presence, expected by 2026, raises questions about Baghdad’s ability to address the threat of Daesh (ISIS) on its own, especially in light of the parallel US disengagement from Syria. Some sectors of the Iraqi government are reportedly considering postponing the withdrawal of Washington’s troops, while pro-Iranian militias, starting with Kataib Hezbollah, are threatening to resume attacks against US troops in the event of delays.

Regarding militias, the Popular Mobilization Forces remain an ambivalent actor. On the one hand, they are an integral part of the security system; on the other, recent incidents suggest political use of these paramilitary structures, with arbitrary detentions and pressure for votes, in clear violation of the 2016 law prohibiting their association

with political parties.

On the international level, the Sudani government has sought to revitalize Baghdad’s role as a regional mediator, to the point that the dual hosting of the 34th Arab League Summit and the Economic and Social Council Ministerial Meeting (held in Baghdad in mid-May 2025, as part of preparations for the 5th Arab Summit on Economic and Social Development) has been presented as the consecration of the “new Iraq.”

On the other hand, the absence of 16 Heads of State and internal controversy over the invitation to Syria’s al-Sharaa have exposed the fragility of the state apparatus and the difficulty of building a genuine regional consensus, highlighting how Iraqi foreign policy is still subject to internal balances.

Furthermore, criticism of Iraq’s “grain diplomacy” (a donation of 50,000 tons to Tunis to incentivize participation in the Baghdad summit) has reinforced the perception that Iraq is attempting to gain diplomatic legitimacy without first addressing its structural vulnerabilities.

In conclusion, the November 2025 elections will be a test of the stability of the institutional system and Iraq’s ability to overcome sectarianism. Should Prime Minister Sudani succeed in retaining his mandate and maintaining the support of a stable coalition, he will be able to consolidate a pragmatic approach based on development, security, and diplomatic openness in a regional context where new balances have emerged following the events of October 7, 2023.

However, the persistence of intra-Shiite divisions, the dispute with the Kurdish Regional Government, Iranian interference, and the role of militias represent significant obstacles. The great unknown remains voter turnout: a large abstention would risk undermining the new Parliament’s legitimacy, with repercussions for internal stability and external relations. (Photo: Iraq. Election Day. Shutterstock/Sadik Gulec)

Alessio Stilo/CeSI