Kenya. The superpower of satire.

With his illustrations, he strikes harder than any editorial. After living for years in Nairobi, the Tanzanian artist shares a passion that was born early and a reality that never ceases to “inspire.”

Gado, the pseudonym of Godfrey Mwampembwa, was born in 1969 in Tanzania, but has lived in Nairobi for many years. He is one of the most appreciated African political cartoonists. His immediately recognisable sign and his pointed jokes summarise a complex situation in a flash, better than any long editorial.

How did you come to be called Gado?

I have been drawing since I was very young. My mother, who was a teacher, immediately noticed my abilities and supported me by choosing the schools where I could best develop my talent. I published in the newspapers of the then capital, Dar es Salaam, when I was still a high school student. After finishing my military service, I enrolled in the faculty of architecture, but after a few months, I won a competition run by the Daily Nation newspaper, so I came to Nairobi to collect the prize. They immediately asked me to collaborate permanently, but I did not yet have a regular work permit, and so they asked me to sign with a pseudonym. I chose Gado, my “teenage name”, used by my friends to cheer me on during football matches. It was 1992. I was 23 years old.

When did you realise that you were interested in political satire?

I have always had two passions: art and what happens in the world. History and geography were my favourite subjects. I have always tried to read as much as possible. Even as a boy, I listened to the BBC and read magazines, like Time and Newsweek, that my father brought home. The two interests merged into political satire.

What do you like most about your job?

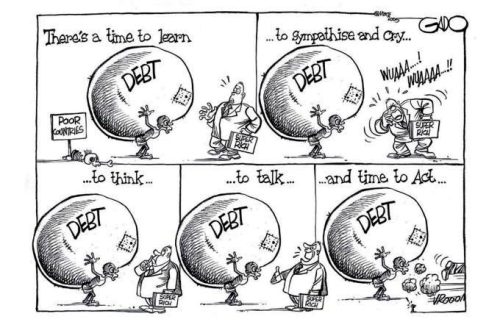

I would say the ability to communicate by synthesising many words in a drawing, laughing and making people laugh intelligently. Doing satire is not an easy job. You need to have a deep knowledge of the topics discussed, and I’m not just talking about information and reports, but also their historical roots and connections. Only in this way can you connect all the dots and express your thoughts concisely and effectively. This is why I have read and still read a lot, especially historical essays and works by artists. All this is the basis of my inspiration.

What margin does political satire have in this period in which authoritarian regimes are asserting themselves?

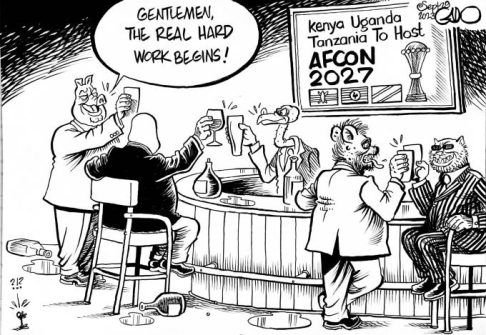

Now, satire is more necessary and important than ever because it reveals the problems of power. Cartoons, in particular, can be especially incisive. This is why authoritarian leaders, from Donald Trump to the president of Kenya, William Ruto, and everyone else, detest satire that has the license to tell the king that he has no clothes. Other registers of communication cannot afford that. Many of these leaders have responded with retaliation these days. Here in Kenya, the young cartoonist, Kibet Bull, was arrested. We recently helped a colleague of ours leave Burundi with his family because he was wanted. In the United States, some have quit their jobs because they were censored, like Ann Talneas, who worked at the Washington Post. Steve Bell’s contract was not renewed by The Guardian. Satire is under attack everywhere these days.

Which African leader stimulates your creativity the most?

I cannot single out anyone. There are so many, and they are all very stimulating. In Kenya, for example, all the work of the Ruto government is a stimulus to satire. You wake up in the morning and discover things that make you say: “No, this is not possible”. In Uganda, Museveni and his son do crazy things. You turn around and find South Sudan, with the eternal Salva Kiir and Riek Machar. And do we want to talk about the DR Congo, South Africa, and Tanzania? Now I collaborate with the weekly, The Continent, and there is so much to say that sometimes you don’t know where to start.

In a corner of your drawings, there is always a very small character that looks like a flower or a small insect. What is it?

It is my alter ego who makes me graphically involved in the drawing. I found it could also be useful to escape the director’s censorship! Sometimes, in fact, he adds a comment, in such small writing that it is difficult to read. But that little man has now taken on a life of his own, and the cartoon does not seem complete to me if he does not appear, too. (Open photo: CC BY-SA 2.0/ Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung – Andi Weiland Laugh out Loud @ re publica)

Bruna Sironi