African Union. Time to choose.

Change at the top. The new Chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC) is fifty-nine-year-old Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, the foreign minister of Djibouti. He faces an organization marked by internal divisions, regional rivalries, and a strong dependence on foreign funding. The AU stands at a crossroads: to strengthen its presence on the continent or remain a prisoner of its contradictions.

The African Union (AU) has made significant progress in its mission to unite the continent and propel it towards a prosperous future. Over the years, we have seen important advances, especially in areas such as regional integration. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is one such achievement that promises to transform Africa’s economic landscape. However, while the AfCFTA lays the foundation for economic cooperation, deeper issues remain that impede real progress, particularly regional rivalries and disputes that threaten to undermine these efforts. A critical obstacle to regional integration is the flawed application of the principle of subsidiarity in Regional Economic Communities (RECs). This principle, which gives regional bodies a leading role in conflict resolution, is undermined in practice by the overlapping mandates of RECs, which compete rather than collaborate.

Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, the new Chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC). Photo AU

In the interventions of neighbouring countries, national interests trump regional peace efforts for simple reasons: political gain or historical territorial and ideological disputes. These dynamics hamper the AU’s peacekeeping mechanisms, with states instrumentalising subsidiarity to prevent independent interventions or manipulate regional responses.

This distortion has led to an ineffective approach, as demonstrated by the cases of the Sahel (where Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have left ECOWAS) and the unresolved conflicts in Sudan and the DR Congo. Rather than facilitating peaceful solutions, the Communautés économiques régionales (CERs) see their influence limited by member states that exploit neighbouring conflicts to strengthen their own positions, weakening regional bodies and hampering the AU’s effectiveness.

What sort of integration?

In addition to conflict, overlapping and competing regional economic blocs undermine the AU’s ability to drive integration. The multiplicity of CERs with different mandates – ECOWAS, SADC, EAC, COMESA and IGAD – generates inefficiencies and policy inconsistencies. The DR Congo, for example, belongs to multiple CERs, each with its regulations and structures, creating complexity that undermines efforts for a unified trade policy under the AfCFTA.

Misera (The Gambia) and Senoba (Senegal) border post on the South of Trans-Gambia Corridor. Photo: IOM/Lamin W. Sanneh

Without clear alignment and a defined roadmap, Africa risks seeing its integration agenda bogged down by bureaucracy and power struggles.

Border closures for security reasons or political disputes hinder the movement of goods and people, contradicting the principles of the AfCFTA itself. There are many examples. Two in particular: the Nigeria-Benin tensions have caused periodic blockades that limit trade and cooperation; Kenya-Tanzania disputes over non-tariff barriers have disrupted trade flows within the East African Community (EAC).

The root of these difficulties is often a lack of trust and unresolved historical tensions. Many states still face colonial demarcation issues that influence current policies, fuelling suspicion and rivalry. Resolution requires diplomacy and impartial mechanisms recognized by all parties. The AU could take a more proactive role here, mediating pre-emptively and providing the CERs with robust tools to manage disputes.

A disunited front on the global stage

The second major challenge is Africa’s fragmented and ineffective voice on the global stage. This is particularly worrying at a time when geopolitical dynamics are rapidly changing and Africa’s potential as an economic and political force is greater than ever. Instead of presenting a united front in international negotiations, Africa’s position is often divided, reducing its influence and bargaining power. Whether it’s climate negotiations, trade talks, or efforts to reform the international financial system, Africa’s approach often revolves around asking for more aid, without challenging the structural barriers that continue to hinder its development.

For example, in climate negotiations, the African position has typically focused on demanding more financial support, even if promises made in previous agreements have not been kept. This focus on aid, rather than regulatory reforms that would support long-term industrialization and economic transformation, keeps Africa trapped in a cycle of dependency.

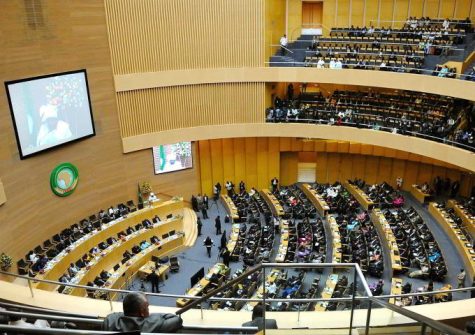

Ordinary Session of AU Assembly. Photo: AU

The current debate over renewable energy and critical minerals highlights this: Africa is again being positioned as a mere supplier of raw materials – lithium, cobalt, rare earths, green hydrogen – needed for global transitions, rather than being empowered to develop its own industries and value chains.

World powers, in particular, continue to treat Africa as a resource base to fuel their green energy ambitions, without recognizing that Africa must not only be a supplier of raw materials, but also a global player in technological innovation. The weakness of Africa’s negotiating position is also evident in global financial negotiations.

While institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) continue to dictate financial terms for many African countries, the continent has yet to achieve significant structural reforms in global financial governance. The AU needs a more proactive strategy to push for debt restructuring that goes beyond short-term relief and instead addresses the underlying inequalities of the global financial system. Further complicating the picture, Africa also lacks a united diplomatic front. Even during critical global events – such as the annual UN General Assembly or G20 summits – African nations may present conflicting proposals or fail to coordinate their negotiating positions, diluting the continent’s collective influence. Greater investment in diplomatic training is needed.

Financed by external donors

The third issue concerns the effectiveness and sustainability of the AU, which is still dependent on external donors, which limits its autonomy and its ability to implement its strategies. Without financial independence and more efficient governance, the AU will remain vulnerable to external pressures and unable to meet citizens’ expectations. Another critical issue is the limited inclusion of civil society, the private sector and young people in decision-making processes. While dedicated forums exist, concrete tools to transform recommendations into policies are often lacking. The greater involvement of young people, who are drivers of innovation and entrepreneurship, could give new impetus to the AU agenda. Building a more robust African Union also requires stronger accountability and oversight mechanisms.

Currently, allegations of mismanagement or corruption within certain departments can be difficult to fully investigate. The creation of an independent ethics commission or ombudsman office could enhance transparency and help restore public trust in the institution.

An active role and valuing young people

If the AU is to realise its true potential, it must stop being a passive observer at the global table and start actively shaping the future of the continent and, indeed, the world. This requires bold leadership, a renewed commitment to regional integration, and a fundamental rethinking of Africa’s role in global governance.

University students in Mozambique. With an average age of 19, the continent has the youngest population in the world. File swm.

Critical to this transformation is harnessing the dynamism of Africa’s youth. With an average age of around 19, the continent boasts the youngest population in the world, offering immense potential for innovation, technological entrepreneurship, and social transformation. By prioritizing education, skills training, and digital infrastructure, the African Union can unlock this demographic dividend.

Intercontinental partnerships

Another area ripe for expansion is that of intercontinental partnerships that respect African sovereignty. The AU could, for example, spearhead agreements with China, the European Union, or other global powers that emphasize technology transfer, local manufacturing, and skills development rather than simple raw material extraction. These partnerships must be rooted in transparency, mutual benefit, and long-term capacity building.

Ensuring that such agreements include clauses on environmental protection, labour standards, and equitable revenue sharing would further protect African interests and promote sustainable development.

Troops of the African Union Mission in Somalia. Photo: AMISON

Africa’s recent inclusion in the G20 provides a platform for the continent to raise its voice, but it also brings heightened responsibility. The AU will need to coordinate and promote a range of policy priorities—from infrastructure development to debt restructuring—ensuring that these discussions translate into tangible results on the ground. If used effectively, G20 membership can help shift the narrative from viewing Africa as a place of permanent crisis to recognizing it as a continent of global opportunity.

The AU is, therefore, at a crossroads. It can seize this moment to address its institutional shortcomings, unite its members under a shared vision and assert itself on the world stage, or it can continue to be weakened by internal fragmentation and external exploitation. The stakes are high.With the right leadership, adequate resources and strong political will, the AU can become the linchpin for Africa’s renaissance in a rapidly changing global order. (Open Photo: African Union flag and African flags. Shutterstock/patrice6000)

Carlos Lopes