Antarctica, the new Eldorado.

Antarctica, although formally neutral and without a stable population, is today at the centre of growing geopolitical tensions related to the management of its natural resources. The historic territorial claims of countries such as Argentina and Chile, combined with the global race for fishing, hydrocarbons and minerals, make the continent a critical point for future equilibrium.

In contemporary geopolitical debates, the Arctic and its trade routes, gas fields and tensions between Russia and NATO are often discussed. Yet, Antarctica, a continent at the antipodes, remains a silent enigma for many. Its strategic importance is less visible but far from marginal.

A continent that, despite not belonging to any state, is at the

centre of global ambitions. The fundamental legal reference for understanding this dynamic is the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, signed in Washington by 12 countries during the International Geophysical Year. Coming into force in 1961, the treaty established the principle of peaceful use of the continent, expressly prohibiting military activities and the economic exploitation of its resources.

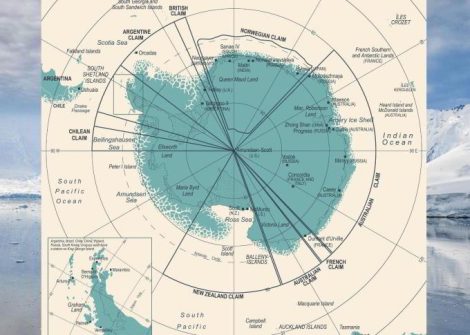

Antarctic region Map. Shutterstock/PorcupenWorks

In reality, the treaty represents a fragile compromise: temporarily freezing territorial claims without eliminating them. Countries such as Argentina, Australia, Chile and the United Kingdom have suspended, but never renounced, their claims.

Today, the balance seems to be holding, but it is creaking under the weight of new geopolitical, climatic and technological challenges. Antarctica has remained a unique scientific and diplomatic laboratory, but its neutrality, guaranteed by an agreement signed over sixty years ago, risks being put to the test. Despite the ban on economic exploitation imposed by the Antarctic Treaty, the continent is a sort of natural treasure chest full of potential.

At sea, intensive fishing – particularly that of krill, the base of the food chain – has already had devastating ecological impacts. On land, the Antarctic soil hides enormous mineral deposits and potential offshore hydrocarbon reserves. Gold, iron, uranium, nickel, oil: resources that are protected today, but at the centre of growing ambitions.

The management of this heritage is based on a complicated multilateral system. Since 1994, the Consultative Parties to the Treaty – only 29 out of 56 signatories – have met every year to discuss the future of the continent during the ATCMs (Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings).

Icebreaker clears its pass in Antarctica. Shutterstock/Mozgova

This is where the strategic interests of the powers, disguised as scientific initiatives, collide. Russia, for example, has the largest fleet of icebreakers in the world, useful for both research and future mining logistics. China, with an expanding network of scientific bases, has installed radar, telescopes and dual-use technologies, which can also be used for military purposes. And Australia, which claims over 40% of the continent, is investing millions to explore and map resources. The risk? That, in 2048, the year in which the formal ban on mining will expire, the fragile balance could be upset. At that point, Antarctica could transform from a scientific sanctuary into a new theatre of global competition. Antarctica is the only continent never colonised, without indigenous populations and inhabited only by researchers.

Yet, since the 1940s, it was clear that it would not remain outside the power games. After the Second World War, it was thought that the United Nations could administer it as a common good. But the rivalries that emerged during the Cold War – especially between the USA and the USSR – caused the idea to fail.

Science exploration at the South Pole. Shutterstock/Mozgova

The 1959 Treaty was a compromise between states with direct interests, but already in the 1980s, it was criticised for its elitist nature. Countries of the Global South, in particular, were calling for more inclusive governance. Today, Russia and Australia are emerging among the protagonists of the Antarctic scene, but China and the USA also maintain a strong and growing presence. In January 2025, Chilean President Boric visited the South Pole, underlining Chile’s territorial claims and its environmental and strategic concerns. A symbolic gesture, which hides the anxiety of a minor country caught between geopolitical giants. China maintains the largest fishing fleet in the Antarctic, operating year-round. Russia continues its geological surveys, given a possible post-2048 change of rules. The United States is watching, ready to counterbalance. It is a silent race, made up of scientific bases, investments, satellites and diplomatic flows. Antarctica, frozen and distant, is already the testing ground for 21st-century geopolitics: a continent that belongs to no one, but that many would like to control. (Open Photo: Huge Arch-Shaped Iceberg in Antarctica. 123rf)

Riccardo Renzi/CgP