Music. Cape Verde. A dance lasting half a century.

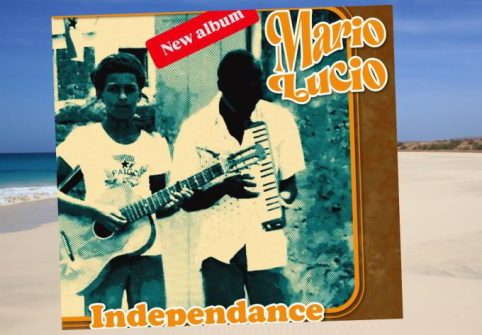

Musician, writer and politician Mário Lúcio celebrates the 50 years of the independence of the archipelago with his seventh work ‘Independance’. A non-random Frenchism, which tells of Pan-Africanism, struggles and the joy of freedom.

In January 1960, in Brussels, when the date of independence of the Belgian Congo, June 30, was set at the negotiating table between Belgium and the Congolese delegation, Joseph Kabasele launched his Indépendance Cha Cha. The musician, known as Le Grand Kallé and a crucial figure in modern Congolese music, was present with his band in the capital to support his compatriots engaged in negotiations: in French, the indépendance of the title rhymes with danse, and all of black Africa in the years following 1960 – the year in which seventeen African countries became independent – would dance wildly to Kabasele’s Indépendance Cha Cha.

Not all of them, to be honest: for example, not the Portuguese colonies, who had to wait for their liberation movements to wear down the fascist dictatorship of the Estado Novo, until April 25, 1974, when the uprising of the captains of the Portuguese armed forces brought down the then Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano.Cape Verde became independent on July 5, 1975: it was only in the mid-1970s that the archipelago – which since colonialism had been kept facing Portugal and with its back to Africa – could re-embrace the music of the other countries of the black continent, and it was only then that it could return to practising in the light of day the traditional dance music that had been discouraged or – like the funaná – severely prohibited by the Portuguese.

Vertigo of freedom

In the memories of Mário Lúcio, who was ten years old at the time, the emotion of freedom is one with the contagious atmosphere of dancing in a Cape Verde without any more masters: for this reason Lúcio, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Cape Verde being free from colonialism, titled his seventh, joyful personal album not Independência, in Portuguese, but Independance, as in French, precisely to preserve that rhyme that he had personally experienced as a teenager: but it can also be taken as a title in English, and then it is a play on words between independence and dance.

Mário Lúcio in concert. Facebook

Mário Lúcio began to be attracted to music while still a child, and to play, with other peers, often with rudimentary instruments, in the years before independence. Born in 1964 on the island of Santiago, in Tarrafal, the city of the infamous prison where the Estado Novo deported opponents from Portugal and all the colonies, Mário grew up with seven brothers in a Cape Verde that Portuguese colonialism condemned to poverty and backwardness. A very precocious child, at eight years old, he was writing poems and drafting in Portuguese the letters to migrant husbands that the women dictated to him in Creole. At ten years old, he was entrusted to the soldiers of the newly formed Cape Verdean army, who had transformed the former prison into a barracks: this was to his benefit since, at the age of twelve, he lost his father, and then, at fifteen, also his mother. During his adolescence he would play the guitar and sing in a group that called itself Abel Djassi, the clandestine battle name of Amìlcar Cabral, the charismatic leader of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea (Bissau) and Cape Verde, assassinated in ’73 by Portuguese hitmen; Lúcio, who was also an established writer, published, in 2022, A Ultima Lua de Homem Grande, a splendid novel about Cabral’s last twenty-four hours.

He is considered to be one of the most important exponents of his country’s music. Facebook

His new album aims to be a celebration of independence through dance, but certainly without leaving history aside: in one song, Rabidante, Lúcio evokes the “camarada Abel”. In 1984, thanks to a grant from the Cuban government, Lúcio was able to continue his studies in Havana, where he attended university but also discovered the Afro-Cuban musical heritage. It was there that he was influenced by the great singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés; he formed a group and became interested in European composers such as Kodali and Bartok. In 1990 Lúcio returned to Cape Verde with a law degree and practised law in the capital Praia. In 1992, he was among the founders of Simentera, one of the most important groups in modern Cape Verdean music, with which he remained until 2004.In the meantime, between 1996 and 2001, he was in parliament, elected for the PAICV, Cape Verdean heir of the party that had led the fight for independence. Having left Simentera and also his job as a lawyer, in the new millennium Lúcio continued with a personal career, establishing himself as one of the most important exponents of his country’s music, also as an appreciated and much sought-after author of songs for other performers.

From 2011 to 2016, he was also the Minister of Culture of Cape Verde. CC BY-SA 4.0/Mario Lucio Sousa

From 2011 to 2016 he was also the Minister of Culture of Cape Verde, in that role creating among other things the Atlantic Music Expo, an important annual showcase for the music of the archipelago. In interviews given on the occasion of the album’s release – which ends with a track for which Lúcio used a recording featuring the late Cameroonian musician Manu Dibango – the Praia artist stated that he sees independence as a process, more difficult than reaching the moment of independence itself; and in terms of balance, he told the Cape Verdean website inforpress: “Independence means going from 75 percent illiterate to 98 percent literate in fifty years, from zero to eleven universities, from two to fifty high schools: it was worthwhile.” (Open Photo: Mário Lúcio. Facebook)

Marcello Lorrai