Witnesses of the Jubilee: Father Ramin, Martyr of Hope for the Amazon Forest.

“I love you all and I love justice. Let us not approve violence, even if we are treated violently. The Father who is speaking to you has received death threats. Dear brothers, if my life belongs to you, so will my death.” Forty years have passed since the murder of Father Ezechiel Ramin, a young Comboni missionary in the Amazon Forest.

As the old jeep moves swiftly along the narrow, dirt road through the forests of the Amazon, the sunlight streams down through the thick undergrowth and the eyes of the curious follow the movement of the car. The situation is becoming difficult and Fr. Ezekiel feels the tension, aware as he is that armed conflict could break out which would affect the families of the peasants most of all. They and their many children.

For some weeks now, a group of families had occupied land on the Katuva ranch, whose property had been illegally occupied by some farmers of the area.

The ranchers had set up roadblocks with heavily armed guards on the approach roads, thus isolating the peasants.On the previous day, Fr. Ezekiel, together with the president of the rural union of Cacoal, Adilio de Souza, had visited the nearby community of Road 7. While speaking with those settlers, he had told them they should do something immediately about the case of the peasants on Katuva ranch.

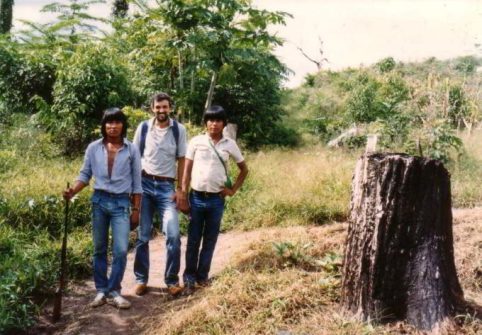

Father Ezechiel and two community leaders. “Justice is achieved by peace, not with weapons. File swm

After the meeting, he had agreed with Adilio to go the following day to Katuva to meet the peasants, reassure them and advise them not to make the situation worse.

And so, early in the morning, he left with Adilio and arrived at 11.00 am at Katuva Ranch, in the municipality of Aripuanà (Mato Grosso), about 100 Km from Cacoal.

Fr. Ezekiel immediately had a meeting with a dozen or so people. He advised the peasants to steer clear of violence and said, among other things: “You must be patient for a few more days. Justice is achieved by peace, not with weapons. If you take up arms, you will come off worse, because the others are too powerful. And that is what the pistoleros want, so that they can wipe you out, under the pretext of legitimate self-defence”. The meeting was quite short and left Fr. Ezekiel convinced that he had persuaded the farmers to stay calm and not to resort to violence. Afterwards, he and Adilio set out on their fateful return journey only to find the road blocked after a few kilometres by an off-road vehicle.

Before they could realise what was happening, a machine gun and pistols opened fire on the Jeep. The fire was concentrated on Fr. Ezekiel; in fact, he was struck by more than 100 bullets. Adilio was only slightly wounded; years later, it came to light that Adilio had worked in collusion with the assassins. He had led the priest to his death.

Hearing the shots, some peasants approached, but could do nothing to help. Fr. Ezekiel was already dead, lying in a pool of blood. One of them left on foot for Cacoal, reaching the town late that night and informing the Fathers at the mission. Having spoken with the Bishop, they decided to go to the place of the shooting, where they arrived three hours later.

In memory of Father Ezechiel in Rondolândia, Mato Grosso. File swm

Fr. Ezekiel was lying fifty metres from the Jeep, his body riddled with bullets and shotgun pellets. His shirt and trousers were soaked in blood. His neck had been hit by a close range shot from a rifle. His arms were spread out like Christ on the Cross. His watch was still on his wrist and around his neck there was his coconut chain, a gift from his Surui Indians. His usual sandals were on his feet. The Jeep had not been touched: the keys of the house, the hammock he always took with him to rest in, his personal documents and his camera – nothing was missing. The purpose of the attack was simply to kill Fr. Ezekiel.At that moment, someone remembered what Fr. Ezekiel had said a few days earlier: “I love you all and I love justice. Let us not approve violence, even if we are treated violently. The Father who is speaking to you has received death threats. Dear brothers, if my life belongs to you, so will my death.”

Love is stronger than death

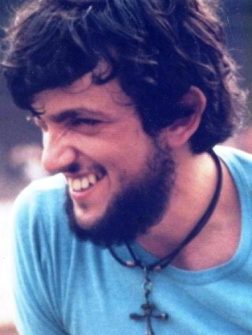

Ezekiel Ramin was born in Padua, a city in northern Italy, in 1953. He attended a local college. In 1972, he joined the Comboni Missionaries, was ordained a priest in 1980, and left for Brazil four years later, assigned to Cacoal in Rondonia, a state in the northeast of the country.

“Love is stronger than death”

It did not take long for Fr. Ezekiel to become aware of the struggle for land that afflicted the entire region. He found himself in a situation of considerable injustice, due to the lack of agrarian reform. Essentially, the situation was one of systematic violence, where the powerful were increasing their holdings by stealing land from the indigenous people, often after killing or expelling them. He once wrote in a letter: “Around me the people are dying while the landowners increase, the poor are humiliated, the police kill the peasants and all the reserves of the Indios are being invaded. My eyes find it hard to see the history of God here on earth. The Cross is the solidarity of God which assumes the process and its pain, not to make it last forever but to end it. The way He wants to end it is not by force or dominion but by the way of love. Christ lived and preached this new dimension. The fear of death did not make him desist from his project of love. Love is stronger than death.”

His commitment brought him into conflict with the powerful and with the authorities. He received several death threats. On 25th July 1985, he died at the tender age of 32, only five years after his ordination.

Private economic interests

More than forty years have passed since Fr. Ezekiel’s death, but the situation remains unchanged. Agrarian reform is progressing very slowly. Last year, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva launched the ‘Land of the People’ programme, which aims to reform agrarian policy in the country by defining the land that can be allocated to family farmers. The executive expects the programme to help resolve agrarian conflicts and increase food production. By the end of Lula’s term, the goal is to reach 295,000 families, of which 74,000 are settled and 221,000 are recognised or regularised in existing settlement plots.

Amazon Forest. Instead of protecting land designated for land reform from mining pressures, private economic interests are given priority. 123rf

Lula’s government has not yet repealed the previous government’s law authorising mining and other industrial projects on protected lands in the Amazon. According to data from the National Mining Agency, as of January 2022, there were 20,000 active mining claims involving land reform settlements. Among the 8,372 settlements nationwide, 3,309 (39%) are subject to mining claims, nearly half of which are in the Brazilian Amazon (1,480 projects, or 44.7% of settlements with mining interests). For Amazon Watch, Brazilian civil society organisations and social movements united in defence of land rights, instead of protecting land designated for land reform from mining pressures, private economic interests are given priority. This trend underscores the increasing normalisation and acceptance of the preference given to economic interests over land redistribution and food production policies, which are essential to address social, environmental, and food inequalities.

Pedro Santacruz