“Islam Needs Illuminism”.

Islam must rediscover the tools of reason and the tolerance of origins. Thus, reopening the minds of Muslims on human rights, women, and religious freedom. And updating jurisprudence, says Turkish intellectual Mustafa Akyol.

It all began with his arrest at Kuala Lumpur Airport, a modern Malaysian city where, even today, they have religious police. Mustafa Akyol, a Turkish intellectual, forced to reside in the United States, landed there in 2017 to attend a conference, but was arrested for suspected apostasy for having declared, in fact, that the religious police should not exist because ‘faith cannot be imposed by the police’.

He would get off with a night in his cell because the former Turkish president Abdullah Gül, still influential within the Malaysian monarchy, intervened on his behalf. But it is from this event that Akyol begins his reflection in his book: ‘Reopening Muslim Minds: A Return to Reason, Freedom and Tolerance’. Explaining complex ideas with engaging prose, Akyol borrows lost visions from medieval thinkers to offer a new vision of the Muslim world on a range of sensitive issues: human rights, women, religion, and religious freedom. Akyol offers a hopeful vision for the future. A third way that is widely discussed in religious and intellectual circles throughout the region, after the advance of the self-styled ‘Islamic state’ catalyzed the debate, clouding the most tolerant views.

How do you view Islamic civilisation?

Islamic civilization has been a crisis civilization for decades. Historian Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975) argued that the Islamic world in the modern era can be compared to that of the Jews of the first centuries, during the epoch of Jesus Christ. The Jews had a very high opinion of themselves, but they had to deal with the occupation and government of the Roman Empire.

Turkish intellectual Mustafa Akyol. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Malaoffice

That Roman challenge can be compared to the Western challenge faced by Muslims today. The Jews at the time developed two different reactions: those who imitated the Romans and were co-opted, and those who opposed them. Toynbee saw twentieth-century Muslims at a similar crossroads. In the 21st century, there are regimes that show their modern face, but make use of internal repression, and others that totally reject modernity. These are antithetical positions that are also found in the academic world.

If I, a Muslim, criticize even just some legal interpretations, I am accused of being an orientalist, that is, of seeing my own culture with a distorted lens. This is an anachronistic and obtuse view.

Is there a third way?

Of course. It consists of recognizing this crisis and making progress. I am convinced that the first Islamic interpretations must be recovered, such as those of the Arab theologian of Islamic Spain, Ibn Tufayl (better known as Abubacer Aben Tofai, author of ‘The Self-Taught Philosopher’ and Ibn Rushd (better known as Averroè, ed.). According to all of them, Muslims have every right to study religion, using the tools of reason, because Islam does not forbid it.

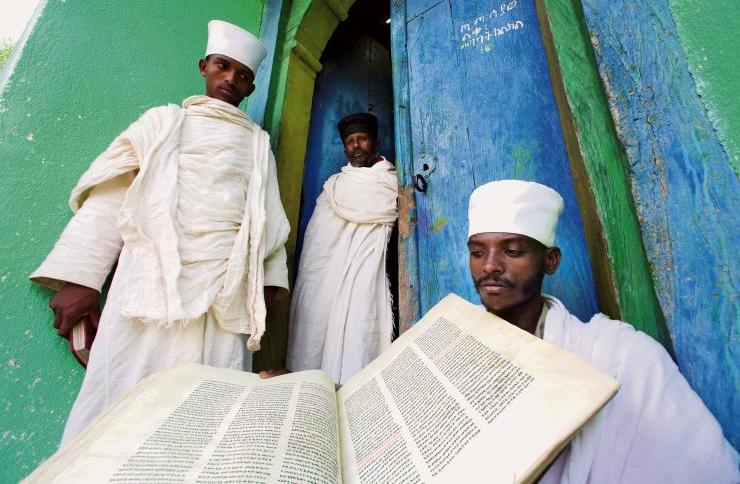

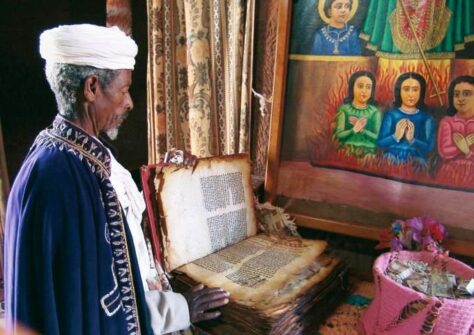

Muslim people in mosque reading Quran together. 123rf.com

Theories like these are the oldest, the most open and tolerant. Although less known, they are often forgotten. In the first centuries of Islam, there was much more diversity and intellectual vivacity, especially in the more cosmopolitan centres such as Iraq, where Sunnism and Shiism coexisted side by side with Christianity. It was the most prosperous and glorious era of Islam. But then, those who have managed power over the centuries have considered them uncomfortable theories and labelled them as heretical and giving them a bad name.

Are some reformist interpretations of Islam condemned today?

I am thinking of Nasr Abu Zayd (1943-2010), in Egypt. Convicted of apostasy, he had his marriage annulled because of his liberal views. He was a great defender of religious freedom, convinced that individual freedom is an essential requirement of faith. So, it’s not just me working on this project to reopen Muslim minds. The Islamic Modernist movement has been calling for a reform of the shari’a since 1800. And Islamic feminists have played a decisive role in women’s emancipation, re-reading the scriptures hitherto interpreted only by men.

You are hoping for a new illuminism in Islam. What do you have

in mind?

The illuminism I have in mind is purely religious. Islam must embark on a process similar to that already experienced by Christianity and Judaism. When Christianity had its crisis, it sought a solution internally, questioning some doctrines, attitudes, rediscovering its roots in the

first age of Christianity.

Quran, The Holy Book of Muslims around the world. 123rf.com

There have been Christian and Jewish philosophers and intellectuals who over the years have reinterpreted these religions with a view to tolerance. Now it’s up to Islam to take this path.

Nevertheless, even today people are condemned for blasphemy and apostasy…

There are those who think that Islam is the only source of wisdom and morality, that those who are strangers to it live in a state of ‘jahiliya’ (ignorance of the pre-Islamic era, ed.) and therefore cannot contribute to the development of society with their thinking.

Originally, Islam had a much more universal vision and today we know that there has also been an accumulation of wisdom brought by Christians, Jews, and atheists. When this view becomes prevalent, the condemnation of apostasy will lose its value.

Must there be, then, a strategy of tolerance to reopen Muslim minds?

I prefer to speak of a theology of tolerance. Reading ‘Dabiq’, the magazine of the followers of the self-styled Islamic state, I realized that the worst heresy for them is that of the ‘murji’ah’, a sect known for its tolerance and support for the idea that judgement belongs only to God and not to other Muslims. The theology of tolerance dates back to the first era of Islam: we can go back to cultivating it and even globalizing it. This tolerance must be applied both inside and outside Islam.

Has this phase of illuminism already begun?

Yes. And not just in terms of reflection. There are Muslim communities living in a context where this process is taking place. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there is no reference to ‘shari’a’ in the Constitution.

In Indonesia, the most populous Muslim country, non-Muslims cannot be called ‘khafir’, infidels.

It is true that there are still radical fringes who want to apply certain rules of Islamic law to the letter, such as cutting off hands.

Arabic Lantern. 123rf.com

The spectrum of Muslims, however, is much broader and many are convinced that there are no longer the conditions to implement those rules. I think that these radical measures should be renounced in principle: not only because they are not applicable in many contexts today, but because the original teachings of Islam did not foresee them. The jurisprudence that has established itself was built up in an era of empires and conquest when the norm was not peace, but war; whoever believed in another religion was considered an enemy. An era that we are happy to have left behind. Now we need to update our case laws. (Open Photo: The Blue Mosque in Istanbul. 123rf.com)

Azzurra Meringolo