Guinea-Bissau. The Gospel and Social Promotion.

Schools, female entrepreneurship, microcredit. These are some of the initiatives of the Oblates of Mary in this small African country.

Cacine is a village of mud-brick houses, covered with metal sheets or palm leaves, built side by side along two dirt paths, where hens, goats, and pigs roam, and where children play. This small town of two thousand inhabitants, surrounded by forest, overlooks an inlet of the sea that from the Atlantic Ocean insinuates itself like a snake among the mangroves in the south of the country. The Oblate Missionaries of Mary Immaculate went to Guinea-Bissau in 2002.

Cacine is the third mission of the Oblates in Guinea-Bissau. One is in the capital Bissau where they run the parish of Antula and the other is that of Farim in the north of the country on the banks of the Chacheu river where various development projects have been under way for years, ranging from schools to medical clinics passing through the entrepreneurship of women whose work is the dyeing of fabrics.

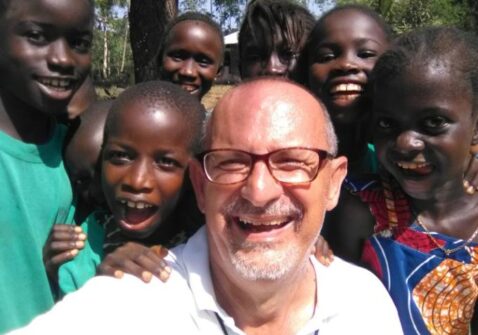

Father Carlo Andolfi, an Italian with 34 years of missionary life in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau, gazes towards the horizon of the sea when the sun turns red in the warm African winter. Every day the missionaries ask themselves how to help improve the lives of these people, how to continue the work of proclaiming the Gospel and developing Christian communities and how to give the new generations an opportunity to grow spiritually and as people.

The answer is their daily commitment that starts with the school. Father Carlo recalls that in one of the nearby villages, Quetafine, a man had started a school under the shade of a tree, to give basic education to the children of the village. Seeing the commitment of this man and the growing interest of the people, the missionaries, together with the local people, decided to build a school and entrust this man with the task of running the small structure. Today that small structure has grown and now there are 6 classrooms and 270 students; with two shifts each day, there is room for all of them.

Sadjo, their teacher, takes care of the little ones in the nursery, while her colleagues patiently teach the older ones: some of those in the second grade who are old enough for secondary school. On each desk, there is a notebook and a pen to copy what the teacher writes on the blackboard. That is all the school material there is. Since the government stopped paying the publishing house that printed the textbooks, it has become difficult to find anything better than a few photocopies.

Outside the school, a concrete base waits for the church to be built; while waiting, the goats sleep there, and some people spread out their rice on it to dry. There is also a school in the village of Cafal, but we are only at the beginning. To visit it, Father Carlo must take the morning boat to cross the sea inlet; he leaves around 10, sometimes even later. There is no precise time so everyone waits on the shore, some with piles of chickens with their legs tied so they can’t run away and some selling fish balls floating in a green broth in small plastic bags.

The crossing takes a quarter of an hour and, on the other bank, we take moto-taxis for the hour-long trip along forest paths, dodging the vines with our heads and holding on to the young and reckless drivers. At last, we reach the small village of Cafal. In addition to accompanying the Christian community, the missionaries also started a school there.

On the waterfront, among the cows licking the salt left by the high tide, there is a group of fishermen. One is from Sierra Leone, another is from Liberia and a third is from Ghana. They have come from neighbouring Guinea: they left Conakry with two fishing boats which were confiscated after they were caught fishing without a permit in Guinea-Bissau waters. For twelve days they have been waiting on the small concrete pier for their boss to send the money to pay the fine and be able to set sail. Even for local fishermen, it is not easy to get something from these waters. Since the Koreans bought the fishing rights, the bulk of the catch is frozen and shipped to Asia. And so, the pirogues made from very light fromager wood, so agile on these placid waters, rest on the sand bringing very few fish for the cooking-pots of Cacine. We are satisfied with rice, at least that is not lacking. Farm animals are slaughtered only on important occasions; chickens are eaten a little more often.

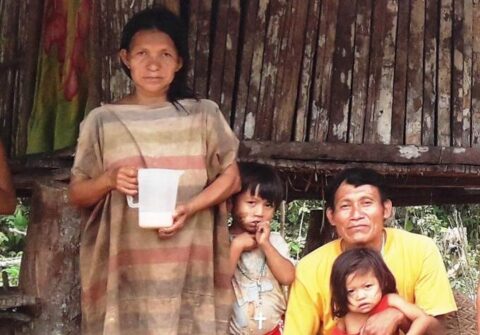

While one young woman draws water from the well to bathe her child, another prepares her bag for the savings group meeting. Her name is Damiana, the animator of five groups of the SILC project (Saving and Internal Lending Communities), in three villages. It is funded by the CRS (Catholic Relief Service – Caritas USA). One of the biggest shortcomings is education in how to save: what you have in your pocket, you spend. Father Carlo says: “Those who join the project deposit a weekly sum, creating a fund which they can then draw on to make important purchases for their families or to start profitable activities, such as buying seeds to produce a crop for sale”. This is but a first step for the new generations in understanding how to become independent and how to bring new development to their community. Open Photo: ©tiagofernandezphotography/123RF.COM

Andrea Cuminatto